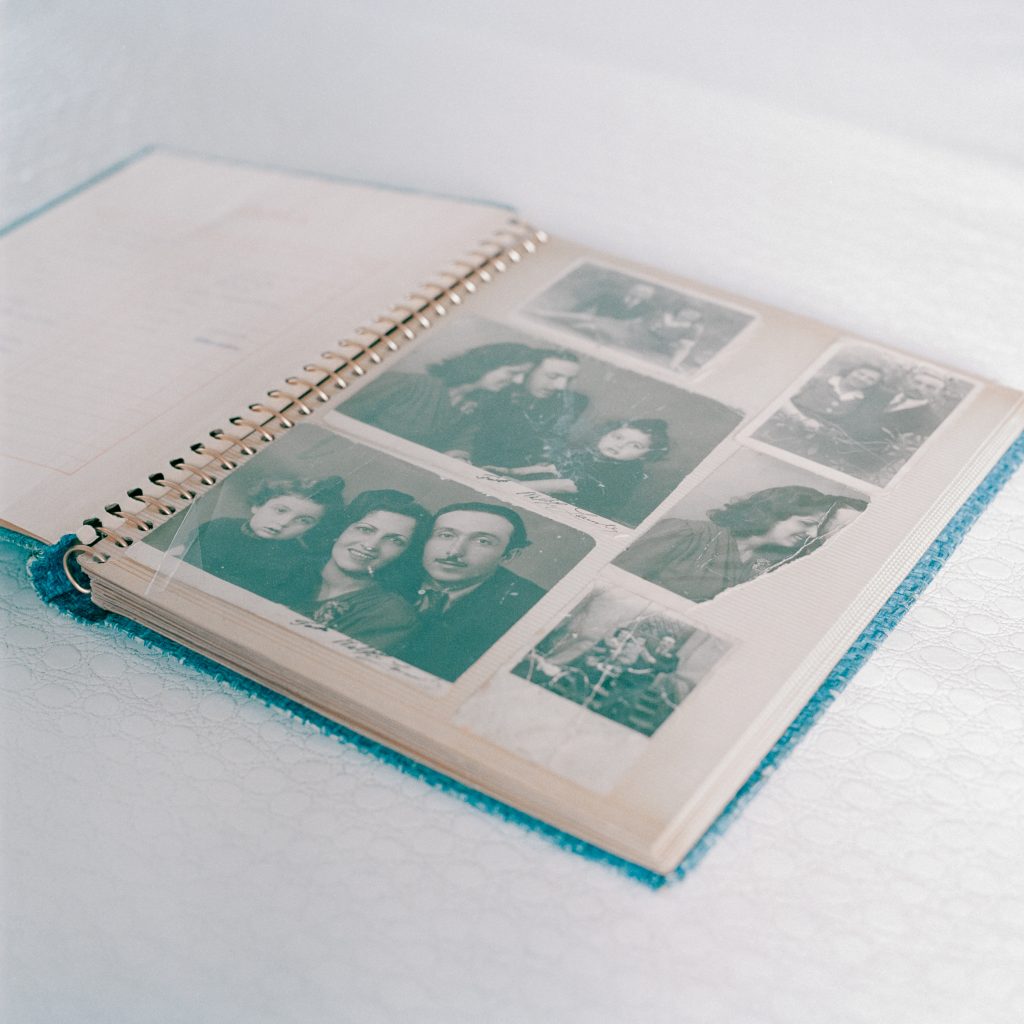

Frieda Gelber

Frieda Gelber (1925-2019). New York, United States. 30 October 2017.

I went to Auschwitz-Birkenau and after that I was only a year in the concentration camps.

In Romania, they didn’t take [Jews] until the last moment – in 1944. But in Russia and Poland, they took them from 1939.

We were all in a ghetto but my sister lived in another town. They took her husband away when she was pregnant. After that she had a little boy, he was named Herzi.

My first experience was terrible. We travelled for three days and three nights on the train until we arrived at Birkenau. Then everybody got off and Mengele was standing there. I got off and he said, “Du Swartze, comme hir” because I was dark skinned. After that my sister came with her little boy and there was a big truck with kids. They grabbed her little boy and they threw him in the truck with all the others. It was unbelievable: a truck full of kids. They just threw them in, like wood.

My mother and father were already in the forest. [The Germans] said they were going to take a shower and we younger ones went to the right, also to take a shower. From there they went straight to the crematorium: my father, my mother and my whole family.

Us. They took us to a real shower. We showered and they shaved our heads. They gave you one piece of clothing. And we stayed outside the whole night until they had arranged which block we were going to go into.

In the morning we had to stay for appell [roll call]. You had to stand in line to be counted. Then they came and gave out numbers. I was there every morning when it came from the chimney – the smell from the people. I was always falling over, when they gave out the numbers I was always on the floor. One [guard] kicked me, and he said he thought I was going to die anyway, so why bother with the number?

Finally it was arranged where we were going to sleep. My block was 14. My number was 1929-40. And I had the number here on my arm – they couldn’t put it in the normal place because I was on the floor.

The girls were all young. The older ones went to the crematorium. We got there and there was no bathroom so in the morning there was an unbelievable smell. The SS said we were going to go to work. They arranged for my group to carry wood to make the train tracks.

I was a little girl, and there were other ones, tall ones. They arranged them, five in the front and five in the back. The tall ones had to carry [the wood] and, as I was the short one, I didn’t feel it. We had to dig lines to make train tracks. The flesh on our feet was falling off from the heat.

In the morning we got a coffee and, for supper, we got a piece of bread. And they gave us soup to eat after doing 12 hours of work. Soup that they cooked with moths, with everything. If you ate it, it was like sand in your teeth. I didn’t want to eat it so I said to the guard, “No, no, no. Don’t give me this, please, don’t.” So he threw it at me and it burned me all the way up.

We struggled with the work. I was 17 but I was so short and so skinny. I was not considered a woman. They took everybody to a building as big as a house. It had holes and you had to stand on your feet to [go to the toilet]. If it went somewhere else, you got hit over the head. You had to make sure you were going in the holes.After that, bread, and then we had to sleep. We didn’t know what we were doing, but we did unbelievable things. I can’t even explain to you.

We were liberated by the Russians in March 1944. And the Russians weren’t so great. They were running after the girls and you couldn’t hide. We hid in a place where pigs were kept; we hid there and smelled the pigs for a month.

We were liberated from there and the Russians gave us nothing. All they wanted to give us was vodka. Nobody wanted it. We struggled and we struggled until the end when the war was over.

We tried to make our lives. No mother, no father, I didn’t know anybody. I tried to make a home. We had to fend for ourselves.

It was summer and we wanted to go somewhere, to a town, to a city. We went to a town and saw a woman hanging clothes outside. I didn’t know what to say, but the other girls spoke to her and asked for piece of bread. She said, “Hold on.” She went into the house and brought out two big vicious dogs who chased us. And no bread; she’d tricked us.

After that I went to my hometown [Ruszkova] to see who had come back and who hadn’t. We stayed for three or four months, and there was nothing. My town was full of Russians – no Jews. There was nothing to do and with no money we struggled. I wanted to go to my older brother; I heard he lived in Cluj.

We didn’t have any money for the train. It was dangerous. And when they came to check tickets, we ran to the bathroom.

All the way from Romania, from my town to Cluj, it was maybe five hours. We got to Cluj and there was a home arranged for all the refugees.

The non-Jews had arranged it for us. The Romanians, you know, they were suffering too. And one guy, a Romanian guy, came to where we lived and he said to us, “You want peace, you want food? Come to the city and I’ll show you.” There was a shop with a big sign – kosher meat. He said it’s carne kosher. Carne is meat so we thought he had kosher meat.

But they had people hanging up there. That was those, you know, those terrible people. That happened after the war.

My little girl was born in Germany. We lived a little while there, for four or five years, in a town called Lampertheim.

My daughter got lupus and she passed away. She was 25. So, life is a bowl of peaches. But it has pips too. That’s what it is.