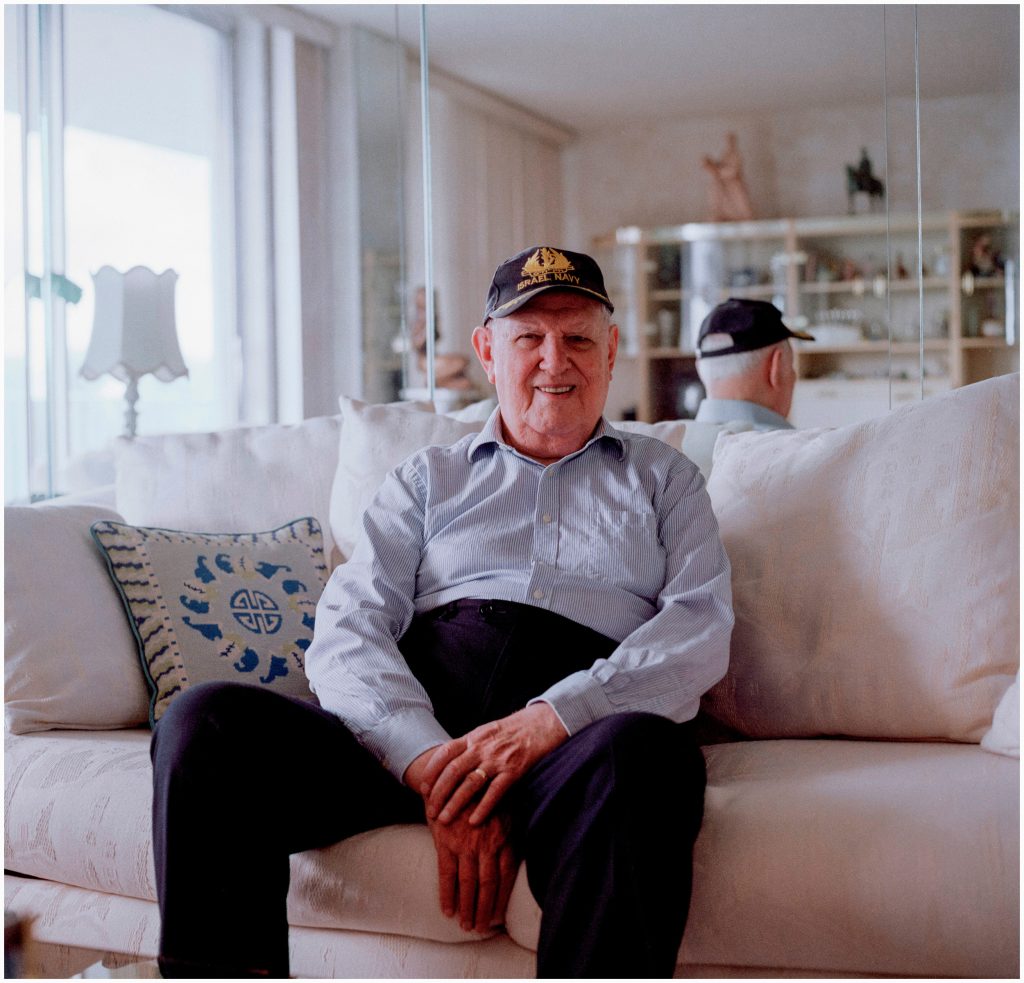

Eugene Lebovitz

(b.1928). Miami, United States. 7 November 2017.

I’m out there because I’m trying to prove something that my mother and father never got to finish, that’s what I’m here for. It’s very, very special if I can convey my message and encourage and inspire kids. I have three very, very important things that I start with: ama – which is love, emunna – to believe, and the third, most important, part is omeh – courage to do what you do: without that you’re nothing.

Fifty years ago Dr Kastner called me up, she said, “Mr Lebovitz, I am also a survivor and I am a child psychologist. Would you give me the honour of interviewing and talking to you?”

I’m telling her about my family. It’s a large family and I’m number nine in my family. My mother had ten kids and she had a very interesting embroidery business that she started. All my life I’m trying to… not imitate her, because you can’t, but somehow live up to her and everything she had done and that she never finished. And that’s why I’m here. To finish her work, and my father’s work.

I was from a large family of ten brothers and sisters, in Uzhhorod [now in the Ukraine]. After the Nazis seized the town, it became the first Hungarian ghetto. I wound up in Auschwitz-Birkenau, having a number, and this number for me is a reminder of knowing where you come from. It doesn’t bother me, I use it as a tool to show people what can happen to a person who becomes inhuman and how you return to humanity, to become a contributor because, in my philosophy, the pleasure is in giving if you have something.

Dr Kastner is the one who really opened up something for me and made me realise something that I really didn’t want to confront. To go back and relive certain moments is very, very hard. I asked myself many times, would I have the courage to escape twice from a death march? Back then I didn’t think. I acted. In order to survive a death march.

I went back [to Auschwitz] a few times with kids. I did that in February, in March, in April – never in January. I was there once in January on the so-called 70th year of liberation, but it was a completely different thing. I was just in the hotel to be at the big [commemoration] in Auschwitz. But in 1945 it was the worst winter Poland ever had. Just a couple of years ago, I realised I had to walk 880 km before I was freed.

I asked the question, ‘How did I do it’? In pyjamas. February, March April. Freezing cold. Very bad weather. I don’t know why but it always blows whenever we are in Auschwitz-Birkenau, the wind and rain and snow.

But how did we children do it? My grandson was with me, seven years ago. He said to me, “Grandpa, you were young.” It’s amazing, the life that you go through and I keep on telling everybody that. Every time I convey my message to someone, I realise that I’m learning the possibility of what you can do, what you cannot do. It’s always the question of you. If there is a will there is a way, but you must have the will first and I learnt that in 1946. When I got here and I saw a sign in Hebrew. It took me a while until I understood but that really became my motto, because if you don’t have any kind of a drive to do that, you’ll never achieve anything.

As they emptied out the work camps, they forced us on a death march in the middle of winter, January 1945. The next day, in the freezing cold and snowstorms, we were loaded into another cattle car and taken to the forest to be shot. I survived under a pile of bodies.

I’m free. This is already the end of March, I’m coming to a village, someone invites me for supper, I don’t take my hat off because they did something, they made one strip, for what reason I have no idea, someone that should recognise you as basically a kid from the concentration camps. I don’t take my hat off and I’m talking Polish very fluently. In walks a German in a black uniform, half drunk. I can see he’s been drinking, he says, “Jew, what are you doing here?” He calls the mayor of that area. This guy comes along and puts me in jail, into a really small room. The door is open, the windows open, people are coming to the window to find out who I am, bringing me food. For three days I’m there and I don’t dare run away. Again, what is the reason for that? I was afraid that if I went out somebody out there would kill me, so for some reason survival became very important. After three days, he takes me back to the concentration camp.

So, I survived and I was put in a block with Russians. Even today I tell people, “You know what the big entertainment at night was? Killing lice.” Full of lice, every one of us was full of lice. No matter how many you killed, they’d come back. So that was the big entertainment at night and during the day we had to dig ditches and do work. I did this for 29 days.

29 April. I am liberated. I look around. I see people come out of the ground like potatoes. This was the first unit, the soldiers. Russian soldiers came out so I realised I had been liberated by the Russians. So, what do I do? I’m the only one that goes to the Russian headquarters. I go there and in front of me they are taking somebody, a Hungarian, and as soon as I see him I start screaming at him in Hungarian. The guy asks me if I speak Hungarian. I say, “da.” He takes me in, gives me boots, the most beautiful pair of boots, pants, shirt, gun and an ID. NKVD. I did not know what it meant. I am the interpreter for the KGB, that’s what the man was. He was a colonel. Ivan Ivanovic, he introduced himself as. Two hours later, after more vodka and a piece of bread, I’m interrogating this gentleman.

“What’s your name?” “My name is Dr Kovac.” I saw by his lapel he wasn’t a regular soldier. I said, “Sir, my name is Eugene Lebovitz. They want to know, they caught you in the forest…” I have no idea who I’m talking to. I had no idea what happened. The first unit picked them up while smoking in the forest. I said, “They want to know which unit you belong to. How did you get here? Who are you?”

He says, “I’m a POW. All I have to give you is my rank, my serial number and my name, according to the law.” I said, “Sir, I am here to interrogate you and you’re going to tell me exactly what they want to know.”

He lays out a plan, he shows me the forest. I thought, ‘My God, I’m the one who was digging ditches in that forest for 29 days.’ Then inside there, in a tunnel, were two units of Germans, one Italian and 100 Hungarians who built that particular thing and they were waiting for the Russians to close in on them.

I go to the railroad tracks. And I see people on a train and I asked, “Who are you?” They’re from all over. I go over there to the sergeant I say, “Sergeant, where are they going?” He replied that if they’re good for the Germans, they can be good for babushka [grandmother]. He used Russian slang and I said to myself, ‘My God, they are going back to be slaves for the Russians.’ I’m reaching for my gun. I’m so furious at that point. Out of nowhere, Ivan Ivanovich – he must have been watching me – says to me in Yiddish, “Get out of here. What you saw nobody knows about.” I tell the driver to take me 20 km, people were telling me I’m close to the Czech border. He takes me there and puts me on a train and that’s it.

I’m on the train to Prague. The conductor comes. “Tickets, please.” I look at him. I smile. I have no money: all I have is God. I take out the ID and show it to him. He salutes me and says, “Thank you.” Now, this is an KGB ID with my name, I’m the interpreter, and on top I realise later on it says Volnutt DS de – travel for free anywhere you want – so I arrived in Prague and look up to heaven and say, “God, thank you.” This is my dream. I wanted to be here as a child.

Out of nowhere, all of a sudden, 50 yards in front of me is a little guy we used to call ‘Four by Four’. So, I walk up to him and he says, “Are you Sigmund’s brother?” I had heard Sigmund, my brother, had been in slave labour since 1941. He got married and a week later they took him. Nobody had heard from him, he became a prisoner of the Russians. The Russians also had POWs, and took the Jews and the Germans.

He hasn’t finished his sentence but a tram came along and I jumped on it. At the end of the street is where my brother lives. I entered and said to the guard, “Tell him Sigmund Lebovitz’s brother is here.” Again, can you imagine? How do you interpret this miracle that within an hour I’m meeting my brother. And he tells me that we have two more brothers alive. I was in shock. One brother was also in slave labour, he was born in 1918. And the other one, four years older than me, born in 1924, was also in a concentration camp. I was born in 1928. How did he survive? We had lost each other. He’d refused to go, so the SS set fire to the barracks. Luckily for him, he was in the corner and when the walls fell down he got out. He just had his ears burnt and that’s how he was liberated.

In January 1945 he was liberated and right away, he goes back to Kraków – this was from Blachhammer. A very unusual place and it’s interesting that he was liberated and he was already back home and so now there are four of us. I’m all alone and all of a sudden there are four of us. Lily Kaplan, who we used to meet at the YMCA in Prague, she told me that my sister was in Sweden, so now there were five of us.

So, here is one miracle after another. Food was still scarce in Prague. One day, I don’t know exactly, the first or second week at the YMCA, a guy walks up to me and called me by my Hebrew name. He said, “Listen, I know you have a special ID and free travel. We could really use you.” I said “Don’t bother me, I’ve had enough. I want to live like a human being.”

A month later, my brother writes to me and says, very simply, how can you sit there and eat bread which is full of the blood of our parents? It was like a key turned and I realised he’s right. I have to do something. The next day I went to the guy who’d spoken to me.

Within two months he says, “I have 36 kids for you. You’re going to take them to Israel.” I think it’s a joke. Really. I don’t take him seriously. Who am I? “All you have to do is take them from Prague to Paris. Just get on the train.”

We arrived in Paris in 1946. Friends from my hometown are there. They knew that we were coming. The communication was unbelievable. And the guy who was in the brigade, who was supposed to have come to Prague to pick them up, couldn’t get a visa.

He was one of the soldiers of the Israeli Brigade. The Israeli Brigade played the most important part after the war in bringing Holocaust survivor kids into Israel. They were the most important part of the whole organisation.

So they told me, “What you are doing is so terrific. Do me a favour: tomorrow night a train is leaving for Brussels. You are going to take them to Brussels.” 36 kids. So, I take them to Brussels, no big deal.

In those days they got on the train at midnight. Then, at six in the morning someone is waiting for us at the station in Brussels and takes us to his summer home. Mr Meyer.

Two days later, the Brigade comes again. I think there were two trucks, each with 18 in the back, and they are driving us to Antwerp. Before we get on, they take away everybody’s ID. That’s when I lost my ID. Even today I don’t know why I agreed to give it to them.

We’re arriving into Antwerp and I see a little cargo ship. I’d never seen a ship in my life. We had special papers [stating] we’re going to South America. Every transport that left from Europe officially had to have these things.

I get on the ship, I take a look downstairs. Even today I still can’t believe how they were going to put people in there. And I see more people are coming, and more people. It took me years to find out that there were 742 survivors. They were down below, where the cargo was. They made wooden beds, and I looked at this and I thought, ‘My God, is this the reason I survived?’

I went up and became very friendly with the captain right away and I said, “Should you need anything, I am your interpreter. Whatever you need.” He spoke a little English. I’ll never forget, he was so confident that he showed me a $100 bill, that’s what he was paid.

And I thought it would be ten days or 12 days. It turned out to be it was 17 days. No kitchen, which means you have no food. And no toilet. Now, how on earth do 742 people survive? Everybody survived. So after 17 days he had the guts to call up the pilot. The pilot takes him into Haifa. He states in the paperwork that we’re a cargo ship with cargo.

And they open up the things and 742 kids come out and the British look at the papers. How on earth does God put me on a ship? My life is so unbelievable, how it started from one to another, and everything had a reason.

The British pick us up. Fortunately I had a wonderful experience and I wasn’t starving like the other people. The Jewish community brought us fruit. I’ll never forget, it the most delicious thing I’d eaten in my life.

And then the next day we were put on some buses and taken to Atlit, with barbed wire. This was a holding camp for the survivors who had arrived illegally in Palestine.