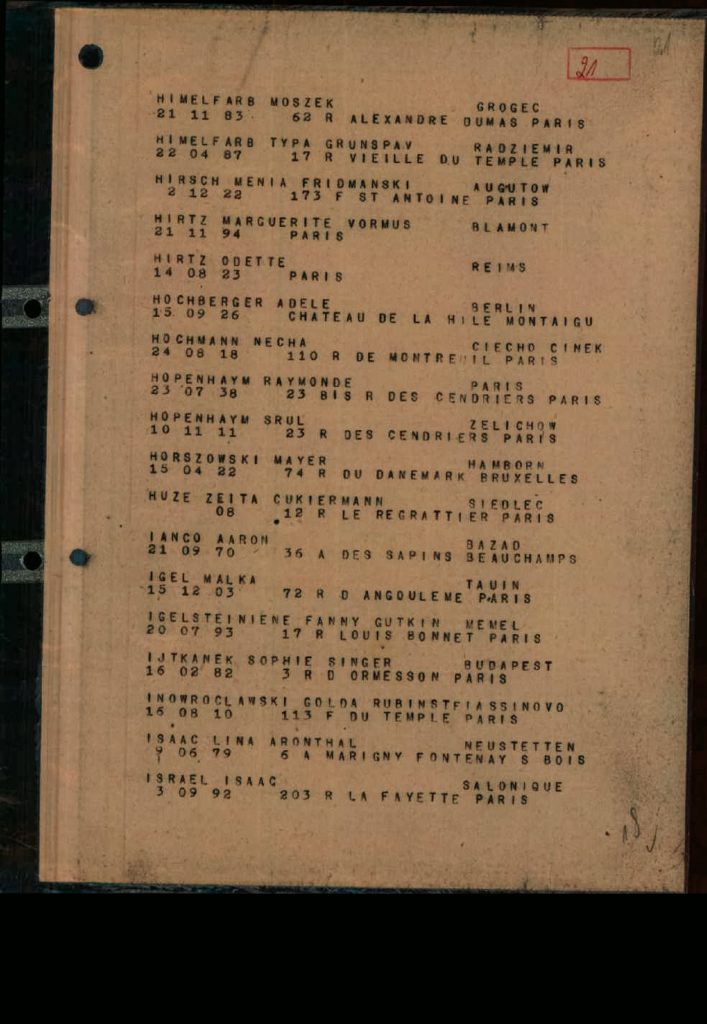

Aaron Ianco

Eliane Wilson, granddaughter of Aaron Ianco (1870-1943). London, United Kingdom. 25 January 2017.

Annie Ianco: When I was five years old, my family lived in the small village of Podu Turcului in Western Moldavia in Romania. It’s there that my life as a child provided my best memories. We were a large family: Maman, Papa, my sisters and brothers. Six children.

My father owned a farm with many sheep and other animals, fields of corn and maize, fruit trees, and also a very small river where the ducks splashed around.

I remember the very warm summers, when Maman allowed us to sleep on the terrace which surrounded our house.

Papa and my two brothers left early in the morning to go to the forest to chop wood for winter. It was dangerous to do it in winter when packs of wolves were howling near the village.

Maman was preparing food for the weeks of cold: apples, walnuts, jams, smoked meat, flour and other things. When she took a moment to rest, I said, “My lovely mother, you are the most beautiful mother in the world, and when I grow up, I will buy you a beautiful castle.” She was laughing, saying, “Yes, my darling.” And [my dog] Mirco was jumping around us.

One morning, as I woke up, everything was white: snow. I jumped out of bed. With shouts of joy, we were throwing snowballs, and each of us made a snowman. We were sledging, taking our skates. Papa made them from bits of iron from an old stove, adapted and adjusted to the shoes with belts. We skated. It was real happiness.

Often, my thoughts go back to my happy childhood, to my village, because later, sorrow came, and much sadness.

I grew up. I went to the village school. My grandfather was living with an uncle; my sister got married. She was 18 years old and was soon expecting her first child. I was ten years old. I was small, very brown, I had braids down my back. I loved to run with Mirco.

I remember, one day, coming back from school, I found Papa and Maman crying. I rushed to them, asking why. Papa told me, “We must leave; our farm and land have been requisitioned by the Romanian government. We have been given three months to get ready and leave. But where to go?” I also cried. To leave my village, my friends, it was not fair. Papa said, “There is nothing we can do.”

My parents wrote to my uncle and he and one of my brothers found a small house for us. We gathered what we had been allowed to take and here we were, on the road in two cars. I was holding Mirco in my arms. I did not want to cry and upset my parents, but I knew that our troubles had begun.

After three days of travelling, my faithful dog Mirco ran away. He had no doubt returned to the village. Maman was consoling me, “He will come back, ma petite fille, he will come back.”

With courage, Maman started to arrange our new home. Papa was very unhappy and looking for work. My brother came to live with us; he was consoling my father and promising him that later he would buy him another farm. As for me, I went to school in a big town; everything was strange. People did not speak to each others; they were walking fast, frightened.

My parents told me that they were frightened by [fascist movement] the Garde de Fer or Iron Guard. Another day, coming out of school, a gang of boys threw stones at me. Thank goodness Mirco had come to wait for me. He frightened them. They ran away, shouting: “Jew girl, Jew girl. We will catch you one day – and your dog, we will kill him!”

Grief and more grief. One day, my younger sister catches a cold. The doctor tells my parents that she cannot breathe any more, because she has croup, a severe illness. There was no time for an operation. He couldn’t give them any hope. The next day, my younger sister closed her eyes forever. My mother threw herself on her bed, crying. Three days later we accompanied her to the cemetery where she sleeps forever. She was four years old.

And woes continued. My brother Maurice did not return. He had been arrested and beaten by the Iron Guard. They did not like Jews. He was in hospital for three weeks, One of his ears was hurting all the time.

The family decided that my brother should go to France, to an aunt in Paris, where he could continue his studies. So he went. He wrote to us very often, promising us that when he got his diploma, we could join him. We lived in hope.

Three years passed. One day, I called Mirco. I found him in the garden, dead, poisoned. I cried and cried. I took him in my arms, my faithful companion. I would miss him terribly. I cried.

Two days later Papa read us a letter that arrived from Maurice. He had received his diploma as a dentist-surgeon. He was already working. He had included our travelling tickets and had rented us a house near Paris.

Our travel lasted four days. Four days of joy. Now we are all reunited and happy. I went back to school to learn French because I wanted to find work and help my parents. I was 20 years old, two years of study. I found work in a bookshop which I liked very much, I could read during my free time. I was happy but, sometimes, I thought of my village. I spent a year in the bookshop.

One day, my brother Maurice told us: “There is a crisis coming. There is talk of war.”

Papa suggested we all come to live with my brother in Paris. One day, I told my parents I had fallen in love. “He is Swiss and with your permission I’d like to marry him. He wants us to leave for his country.”

Immediately Maman said, “Yes, ma petite fille, get married, even if leaving us is a sorrow. Children, in their turn, must create a home and you will come and see us often.”

I left. I was happy. Two years went by. I wrote to my parents that I would come and see them after the birth of my baby [Eliane].

Life in France is very bad and everyone talks about war. Germany is threatening France.

With my daughter I went to see my parents. Tears and joy. My parents had aged a lot. They told me to rush to my husband in Switzerland, this country of calm. When I kissed them, I promised I’d come back but I never saw them again, my darling parents.

War started. Blood and torture everywhere. Jews were deported like cattle, in sealed trains, with nothing to drink, no food, men, women, children. Nobody knew where they were taken.

After the war we learned that six million Jews had been exterminated. My father was among those who had disappeared. My grief was terrible. I had no strength left to cry and I was hoping that Papa had been able to escape. For months and months, I thought somebody was calling me. I would run and open the door crying, “Papa!” But there was never anybody.

Maman too died. Her grief was unbearable Sometimes I think of the little girl I once was. I see myself running with Mirco. I see my parents, my brothers, my sisters. Tears come to my eyes, but my lips are smiling, and I murmur: “Annie, take your pen. You promised your grandchildren [you’d] write the stories of your father, their great grandfather.”

Eliane Wilson: I was a child at the time but I remember my mother holding a letter she had just received from her sister, who lived in Paris. My mother was crying…

My darling Annie, the letter said.

I have heartbreaking news to give you today. Our beloved mother died yesterday. Ever since our dear father was arrested, our mother…

There were thick blue lines hiding and obliterating the rest of the letter. The signature, was all that had been left by the people censuring the post during the occupation.

— Written down in 1992 by Aaron’s daughter Annie Ianco (1910-2000); also told in 2017 by Aaron’s granddaughter, Eliane Wilson