Rita Weiss

Rita Weiss (1926-2018). Tel Aviv, Israel. 4 December 2017.

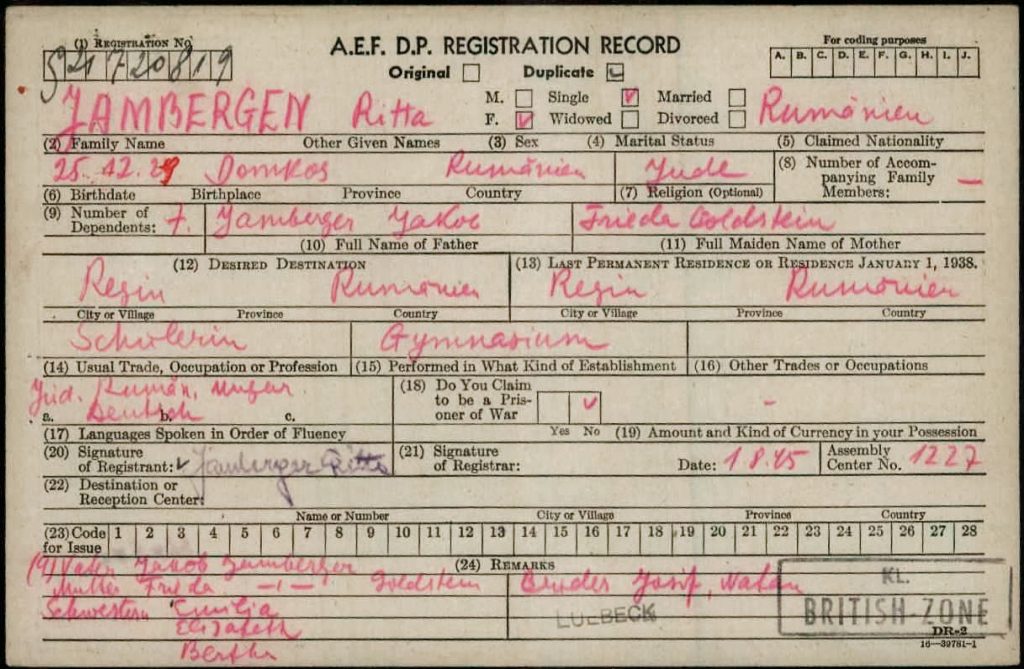

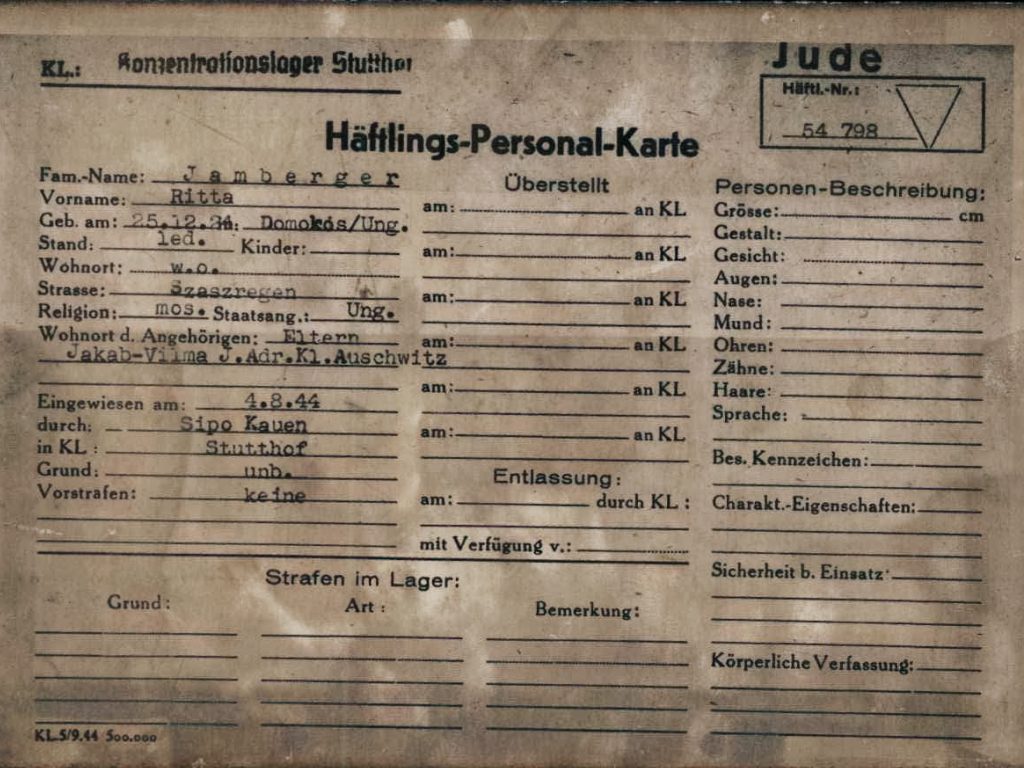

In Stutthof [concentration camp] there were Jewish and many Russian prisoners of war: 160,000 prisoners including lots of women from Hungary. Hungary was only occupied in 1944 by the Germans – before that they were collaborating. We were occupied on 16 March 1944 and six weeks later we were in Auschwitz. I was not with my family because I’d been visiting my sister who was alone with her child in another town, Reghin, and I was not allowed to return to my village. So I never saw my parents and my other sisters again.

They took the Jewish men to a work camp; many of these men were killed. They were made to work in the Hungarian army. One of my brothers was killed in Ukraine – in the snow they shot him. He had three children.

I was born in Domokos in Transylvania. We were not put into ghettos like in the towns in Poland but taken out of our villages and put in a park or onto a piece of land. We did not live in houses with rooms and beds. We had no food.

After three or four weeks, we were taken to the train and into a wagon full of hundreds of people. There was no place to sit. There were two buckets, one for water and one for the toilet; within half an hour the water was empty and the other was full. The camp had three or four thousand people and we were now in 14 wagons. The train stopped so the water could be changed but there was not enough time to get more water as the soldiers screamed for us to go so many wagons had no water. In my wagon was my sister with her child, a boy of four and a half and another woman with a little baby that was maybe just two months old. When the baby died of hunger because the mother had no milk, the mother became hysterical.

In the morning, the train stopped. We had not heard about the camps in Hungary, we had no radio. Nobody knew what was happening in Poland or Germany. They opened the wagon and many men were stood there. We did not understand because they were speaking Polish. “Get out, get out. Fast, fast, fast.” The bags had to stay in the wagon. My sister shouted as they separated men from women. There were many soldiers there, and also [Josef] Mengele. We did not know it was him at the time, only afterwards did we realise it was Mengele. He ordered the people right or left. My sister was separated from her little boy. Another woman cried because they gave her baby away to an old woman. She said, “This is not my baby, why did you give me this baby?” The mother cried and the officer shouted at her to go to the left and she was separated from her baby.

Mengele asked me how old I was. I was very afraid and I could not speak but my sister told me to say 20. Mengele took my arm and said, “You are going right.” The little boy remained alone and cried and tried to find his mother; I think that maybe he did not die in the gas chambers alone, maybe they died together.

We were taken to the showers and our clothes stayed in the first room. We were taken to another room for the shower. We wanted to go back to get our clothes but we were not allowed. We were moved to another place, naked. They shaved our heads and in the middle there was a pile of hair, all different colours. Still naked, we were taken outside. We dressed and they took us to a block and were told not to speak and or look out of the window. In the afternoon we were told we could drink tea. One person asked why they had gone right when the rest of his family had been taken left. “Why is our family not here?” The block commander, who was also a prisoner, said, “Do you not know what this place is? This afternoon your family have gone up in smoke.” We wondered, how can that be?

We were each given a single bowl and we had to look after it. Another morning, the block officer came and told us to stand up. It was still dark. 600 women were taken to the train and we began another three-day journey to Lithuania. It was to a work camp at Krottingen [Kretinga] that was 30 km from the sea.

We could not understand how, just a few weeks ago, we had been in our beds in our clean pyjamas and now we were prisoners in another country. We did not know what had happened to our families. We were in the work camp for just two months because the Russian army invaded and so we were put on the train to Stutthof concentration camp.

We did not know if we were in Germany or Poland. We saw the SS soldiers and commandants for the first time. We 600 girls were under the protection of the Wehrmacht [Nazi armed forces] and could not be taken for selection but we saw many people being hanged. We saw Russian prisoners of war being taken out and hung and all the prisoners had to watch this. We could not look to the ground – we had to watch it. People died from hunger, people died from shooting. There was a boy who was given 80 lashes with a whip.

We had no warm clothes, no shoes, no underwear and we worked very hard in the camp and other workplaces. One time, it was very cold and I fell over but all around the camp was an electric fence. We saw many people run to the fences and be electrocuted. I fell onto the fence and was electrocuted and was burned on my breasts. I saw myself in the air and I saw myself lying in the snow. I thought I had died and maybe I had gone to God. The snow. The cold. I blacked out but in the morning I crawled back to my block and people said, “…but we saw you die.” After that I don’t remember.

In the morning and the evening we had to do roll call to see how many people were in the blocks. Over 1000 people, twice a day, to see exactly how many had died. If you were ill you could not stay in bed, you had to be either dead or standing and [ready to] go to work.

I remember seeing all the people in the camp standing. The men’s block and the ladies’ blocks were separated by a fence, an electric fence. And I saw someone and I thought, ‘Who is this man?’ and I recognised my father. I said, “You cannot be here. Men are not allowed to be here, they will kill you, you must go away.” I began to cry. I mentioned that my father was here but they said I was crazy, nobody was here.

I remember a dream. I see a window and I see my mother and my sisters, my brother. I tap the window and I see my mother. I need to tell her what has happened to me. My mother says, “No, you cannot enter here, you must go. I will not allow you to enter here.” All the people were in white and I believe my family has died because my mother would not allow me to go in.

The Holocaust is not just about the crematoriums. It was about a mother, a young mother. Life was very hard, there was no food, no heat, people died of hunger and this mother, who was in the sixth or seventh month of pregnancy, said, “I will die without food.” In the evening we were given one piece of bread. Her husband said, “I will give you my bread for you and the baby, otherwise all three of us will die.” But I don’t know what happened because at selection we went one way and they went another way. That was the Holocaust.

Another pregnant woman, who was taken straight from her home to Auschwitz, she tried to hide that she was pregnant. But after she had the baby, even though people tried to hide it, they found out. In the morning the SS women said, “Where is the baby?” The two SS women found the baby and took it. The mother went crazy. They shot her from the watchtower. They saw everything all the time. Holocaust.

In April 1945 they ordered us out of the camp. We were on foot. The Death March. We came to the sea and there were barges.

Ronit: They put my mother and the others in five or six barges and pulled them out to sea. The barges had no motors and, after two days, they left them at sea with no water no food, nothing. They were like skeletons.

Rita: We waited to die in the sea. A barge with prisoners from Norway, Poland, Greece. It was April or May, and the sea was not so salty so we begin to drink the water. After one day and one night we did not know what to do. One man said we must begin to swim. We did not know where we were, which country, which sea. We just wanted to swim so we did. We could die in the sea or we could die on the boat. I had to survive, to stay alive, to tell of what had happened.

Ronit: My mother weighed just 34 kilos when she was liberated.

Rita: We saw land and we thought maybe it was Denmark or Sweden but it was not. The water was cold, ice cold. We could not breathe. We heard motorbikes. They were SS soldiers with machine guns and they started to shoot at us. People ran. Blood. Died.

We found a town and searched for food like hungry wolves. We found some in the garbage cans. We heard tanks and we said, “Enough. Thirty times they have tried to kill us and today is the 40th time and I will die. I can’t carry on. I must stop.” I lay down and the tank stopped. But they didn’t shoot. Who were these people? The tank had no SS symbol. It was the English army. We were in Lübeck.

As Rita spoke of being in the sea, I watched as Ronit walked over to her mother and sat on the ground by her feet. Her hand touched her mother’s knee and she held her hand. — Marc Wilson

Ronit: Whenever I think about this story, I think about my mum going from her parents’ home, going to Auschwitz, going to Krottingen, going to Stutthof, and in every period of time she loses more friends, more people around her. She becomes thinner and weaker and she is so young but she wants to survive. And then, after the war is over, they are in the middle of the sea; in the cold, she swims. I don’t know where she gained the power to do it. The soldiers are shooting at her and her friends, and then the garbage cans, and the tanks are coming and it could be the end, but it isn’t. This is a miracle.

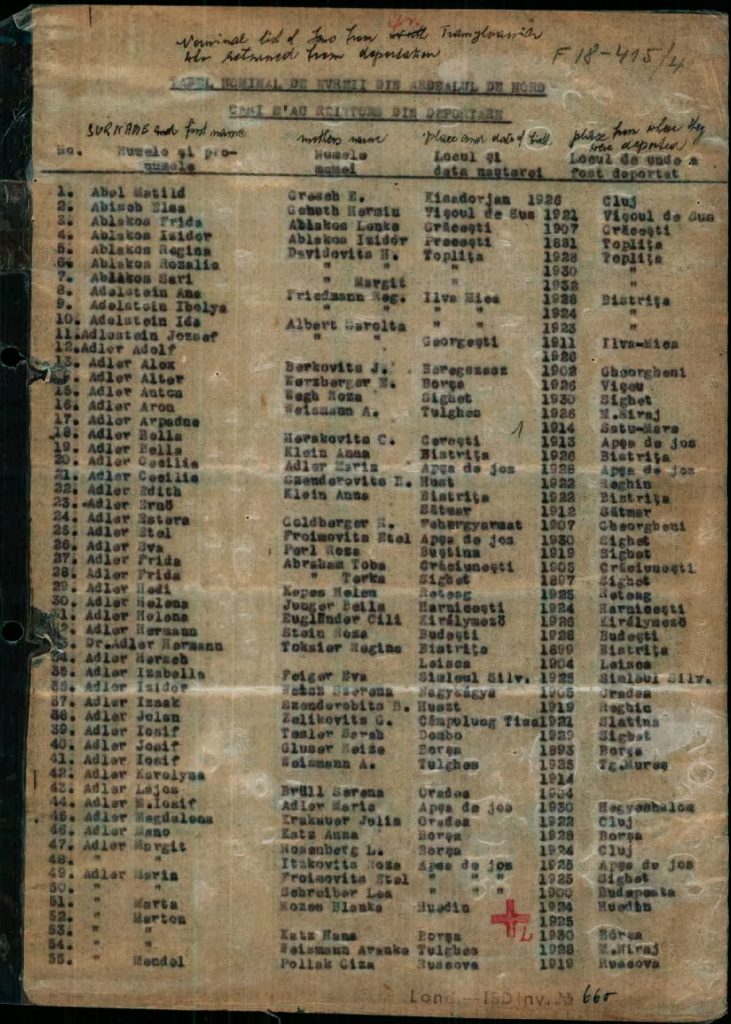

Rita: Afterwards they took us to hospital and listed our names and where we were from. We had nowhere to go. We heard that Bergen-Belsen was nearby and that the English had liberated it. There was no train, no bus. We walked and someone asked us where we were going. We replied that we were going to Bergen-Belsen; they said that it was nearly 200 km away. We were told that there was a list of survivors there. I looked for my family but there was nobody. I had 12 brothers and sisters. Eight of them were killed in Auschwitz.

We remained in Germany, in the camp. An organisation arrived from Palestine to meet the survivors. All our parents had been murdered in Auschwitz so we decided to move to Palestine. Everything was lost.

— Told by Rita, with additional contributions by Ronit, Rita’s daughter