Vladimir Genoler

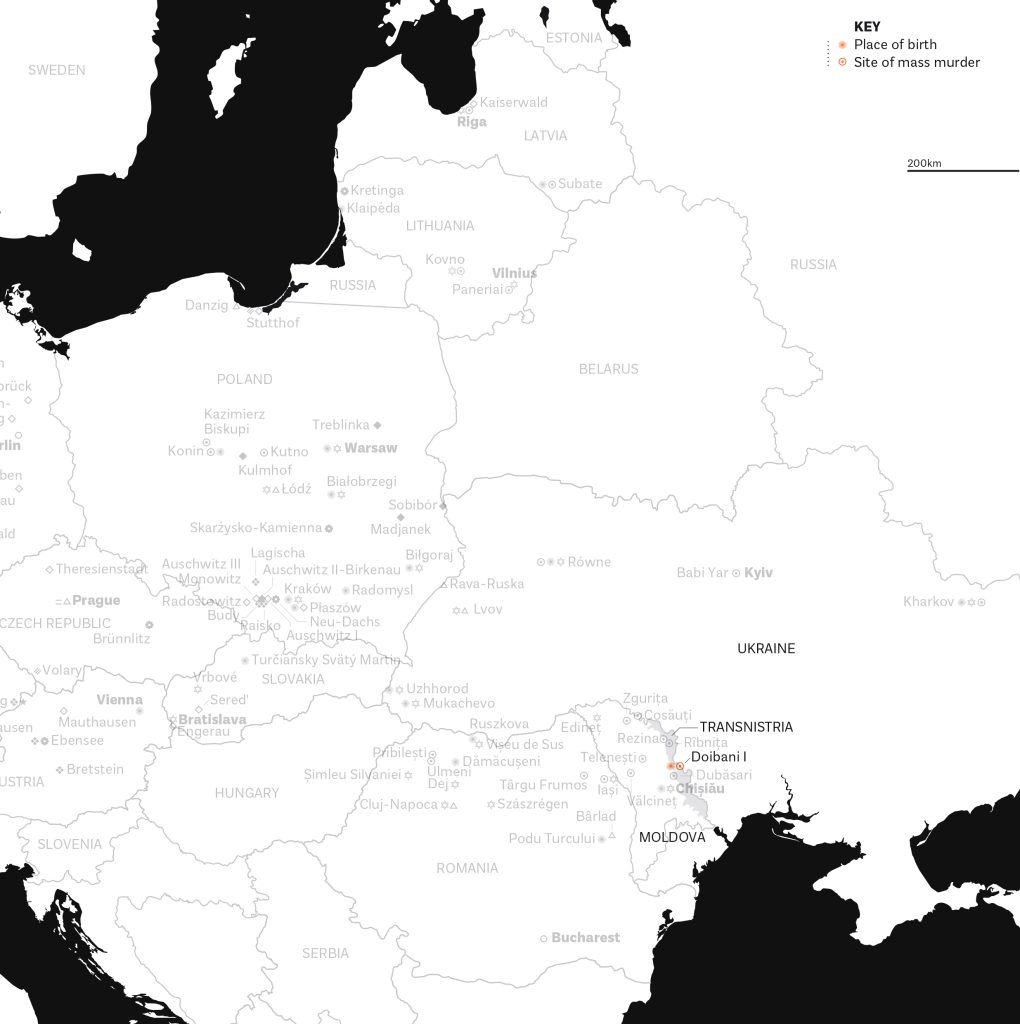

Sergey Genoler, grandson of Vladimir Genoler (birth date unknown-1941). Doibani I, Transnistria. 13 April 2018.

I do not know exactly when my grandfather Vladimir Genoler was born, but he already had five children when he was tortured and executed. My father was just a baby, three months old. He was born in March and it happened on 2 August 1941.

The old people said that when the German fascist invaders came to the village, there were German sympathisers. These so-called henchmen handed over villagers, including my grandfather. He was not a Communist but, as a sympathiser for Lenin’s party, he was close enough to the Communist Party for the Germans. They handed over a list of people who were sympathisers and active under Soviet rule, and also lists of Jewish residents.

People on these lists did not know where they were going; they thought they were just going along to have a conversation, so they went voluntarily when they were called.

The night before the execution, when people arrived in the village council building they were brutally beaten. They were locked in the basement and beaten all night and when they were taken out by these Nazi henchmen, they were beaten along the road. They took them to the edge of the village and forced them to dig their own graves. After that, they began to shoot the Communists and sympathisers one by one, as also the Jewish residents.

They gathered all the villagers and staged a public execution. They forced them to dig graves and, after they were shot, they were buried and covered with earth. The wounded were buried too. People said that for the next two days the earth was still breathing.

Upon the arrival of Soviet troops in 1944, the villagers were allowed to rebury the dead. I don’t know where the Jews were reburied, but the Communists were reburied in the cemetery and everyone has their own grave.

There are no photographs left. My grandmother was afraid that the family might suffer so she destroyed my grandfather’s photographs.

A friend of my grandfather’s had a premonition of what would happen and he left the village the night before the execution. He approached my grandfather and suggested that they run away together; it was easier to run away from the village and hide together. But my grandfather said that he was afraid that his children and family might suffer. He had five children so he voluntarily went to the village council. He knew what could happen. His friend ran away and came back once the Soviet troops had returned.

The son of that man, who was born around 1917, died recently. He gave interviews and when I worked as a police officer I spoke with witnesses. I also had an aunt who saw the executions but she has died too.

We have only one elder left and he can remember it all. I think he was a prisoner then. During the war, he was captured but he escaped and, until the arrival of the Soviet troops, he lived in Doibani, hiding here. He joined the Soviet army and reached Berlin and now he is held in high esteem.

There is another grandfather, Babyan Igor Isaakovich, who was born in the 1920s and remembers the retreat of the German troops. People say that it was sometime in the month of March. The snow melted abruptly and the German equipment got stuck. He remembers dragging bodies to be reburied in the cemetery. He also remembers the execution of the Jews in Koikovo. This was done at night rather than in front of the villagers.

In Doibani II, they also gathered the villagers and demanded that Communists, sympathisers and Jewish residents be given up. But they did not find them because the local people steadfastly insisted there were no Communists or Jewish residents in Doibani II. And so they hid the wounded soldiers and the Jews.

I have one photograph of my grandmother, who hid wounded soldiers and Jews in her house, as well as great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers. It’s from 1910, I think, of my grandmother, still little, and my great-grandfather and great-grandmother. My great-grandfather was a village teacher; Savitsky was his last name. The photographer has a Jewish surname, Britman.

Our family moved from the Kuban region, from Krasnodar in Russia. It turns out that immigrants in Doibani II are supposedly Poles since everyone has a Polish surname. It was a resettlement colony in the time of Catherine II.

According to Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya there are Jewish mass graves. I worked for 20 years in Dubāsari, in the militia. There is a Jewish cemetery. There were mass killings, tens of thousands of Jews were shot.

According to the elders, Dubāsari is a Jewish city founded by a woman named Sarah.

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, merchants on the trade route from Bessarabia [Moldova] to Russia and Ukraine passed through customs in Dzerjinscoe and stopped in Dubāsari. There was an inn where travellers could rest and eat. According to the elders, the courtyard of this inn belonged to a Jewish woman named Sarah and was located under three oak trees. From this comes the city’s name, Dubāsari.

The trade route passed through the villages of Doibani I and Doibani II and for this route the merchants paid two bani – two coins.

— Told by Sergey Genoler, Vladimir’s grandson