Henri Borlant

Henri Borlant (b.1927). Paris, France. 20 June 2017.

My name is Henri Borlant. I was born in Paris on 5 July 1927. I am the fourth in a family of nine children. I say nine children because we have never been more than nine. In fact, my mother had ten children; but one died and I am the fourth. I had a brother, a sister and another brother, then me. My mother came [to France] in 1912, before the First World War, with her parents. She was 12 years old, born in 1900, She had two younger sisters, she was the eldest. They left Kishinev [now Chișinău, Moldova] because of the pogroms, I suppose, and life was very difficult with three young girls. They needed to leave for their security, for their lives, for the lives of their children.

So they came to France. As far as I know they were not rich, they did not speak a word of French. It is very difficult for people like them; there are still many in this situation today. My father did his military service in the army of the Tsar. At this time, in 1912, it was still the Tsar, it was not yet Communist Russia. In the army, Jews were very badly treated. Perhaps he already wanted to leave Russia. Today it is Ukraine but it was Russia at this time, the Russia of the Tsars. And four years later, when my mother was 16, she married my father.

My father was a tailor. He had a sewing machine at home and was given work to do. I know that before I was born and when I was young, he had a workshop in Montmartre. He was already doing work for his own clients. But when I remember him, he worked at home.

There were many children and not much money but it was a happy family with much gaiety because of the small children. We lived like Parisians. We did not eat kosher, we did not go to the synagogue, but the boys were circumcised when they were born and made their barmitzvah. I did not make my barmitzvah because of the war, but my older brothers did.

I grew up in this typically French place – typical Parisian, typical working class. Everybody was the same, working in small trades, with difficulties. It was difficult to feed the children: people were not rich, living in a three-room apartment, with only one water tap.

I was happy because I did not know anything else. We were like everybody else, so we did not eat kosher, we ate at the school canteen like all the young French children and we lived very happily with the little ones. I saw my parents happy to be with their children.

When war broke out, we were made to leave Paris. A couple of days before war was declared, the government said that people with many children needed to leave. As they had no money, no means, trains were organised; no need to pay but you needed to go. We were sent 300 kilometres away from Paris, towards the south, to a village. When we arrived during the night, people took charge to find us housing. There was a small house with nothing inside. They told us, “We are going to lodge you there, then we will look for something else.” There was no furniture, no beds, nothing at all.

My mother gave birth. She was pregnant and in the morning we have one more little sister. I tell you this, and I say it every time because I am a doctor, and I know that a woman who has had many children, when she is pregnant and ready to give birth, she does not move, she stays where she is, she does not travel. It can happen very quickly when you happen to be a woman who has already had nine children. The birth is easy, it takes place quickly. My mother gives birth during the night, we are in this village and, in the morning, one little girl is added to the family. But on the wall there are already posters declaring that war is upon us; it’s the general mobilisation, that means we are preparing for war. On 1 September 1939, three days after our arrival, war was declared.

We had left with almost no luggage. We believed that things would calm down and that we would go back home. My father had stayed in Paris with one of my brothers, the eldest, born in 1917. In 1937, he was 20 years old. He did his obligatory military service. He served for two years and then the German Army entered France. He was taken prisoner, like many others, so he wasn’t with us. When we left, my father stayed in Paris. He said, “I need to work to send you money so you can eat.”

When war was declared, we understood that we were going to stay in the village and they found us a normal apartment. The names of the children who were old enough to go to school were put down for the school. This area, this village, is very Catholic and our names were put down for the Catholic school. The teacher, who was also the director of the school, was a priest dressed in a black robe.

We learn the catechism, we learn the religion, we learn the prayers. We were baptised. I made my solemn communion. I am a real Catholic, I am a believer and I have admiration for the teacher, the priest, because I am his best pupil. I said that when I grew up, I would do the same job as him.

I leave school at 14. They find me work in the village garage. At that time, everybody was cycling and I was a bike specialist. I repaired tyres and helped with electric repairs. I was an apprentice between 14 and 15.

Then in 1942, on 5 June, I turned 15. On 15 July France lost the war. The German army was occupying part of France and, later, the whole of France. But at that time, it was only a part. German soldiers were in the region where we lived – not in the village, but in the region. And on 15 July 1942, a lorry of German soldiers arrived. They came to the first floor where our family’s apartment was located. They had a list. They came to arrest those aged between 15 and 50. I was 15 and one month; I was on the list.

I rushed to get my things, also my brother who is 17, who worked on a farm, and my sister who is 21. My elder brother was not there. They arrested my mother. For me, at 15 years old, to [see someone] put a hand on my mother…my mother who had spent her life being pregnant, giving birth, breastfeeding, cooking for the whole family, working with my father, sewing. My mother was sick; when walking you needed to stop because she couldn’t breathe.

As a doctor today, I know that she had asthma. Chronic bronchitis. She had put on weight with each pregnancy. A woman in a working-class environment, having a child every two years, puts on five or ten kilos during each pregnancy.

As we had done no harm, we believed that we were being sent to work. I said that my mother could not work in factories, nor work the land, that was impossible. I don’t remember whether I thought of what was happening to me, but only of what was happening to my mother.

And there we are, we are loaded on and have to be quick because they are in a hurry, they are not friendly, these military German Police. They wear metal collars with Feldgendarmerie [military police]. They put us in the lorry; it was difficult to get my mother to climb into the lorry. I am frightened, saying, “My poor Maman, what is going to happen to her?” She is separated from the younger children, from five young children, and from her husband.

And we leave, the lorry stops on the road, stops and then takes other families – Jewish only. We understand that we have been arrested because we are Jewish, not because we did anything wrong. Then we are locked up and the women are separated from the men.

I am with my brother. My mother and my sister are taken somewhere else, we do not know where. We are where the archbishop lives, where the students who want to become Catholic priests go to study. The Germans have taken it, turned it into a prison, and here I am with others in a small student room.

After two days, my father has joined us. He tells us they have taken Maman back to her home and have taken him instead. My father was in good health, a sturdy man. My mother is with the children and my father will work. We weren’t happy to go and work in Germany but it was better like this. After five days, we were taken to the station. We had to climb into carriages that transport goods and animals.

There are no windows, no seats. Nothing to eat, nothing to drink. We do not know where we are going. We do not know for how long, but we are [packed] tightly, tightly. In our convoy, men and women are not together. I say this because on most of the trains that will leave later, the women, men, children, babies and old people will all be together. We do not know how long it will last. There are no windows. We are locked in and the wagons are locked. We cannot open them. We climbed in, they were locked and will only be opened when we will arrive somewhere.

There is nothing in the carriage except a bowl in a corner. It is there to do pipi, caca. Everybody thinks that they will wait until they have arrived, and that they won’t use it in front of the others. For those who will leave later, men and women, it is even more difficult. Here we are, we do not know where we are going. The train can wait for hours before leaving. It will start and then will stop, often. It will take three days and three nights for the journey.

We still hang on until we have arrived. In the beginning, people hold on, do not want to do pipi in front of everybody. But when you need to, when you cannot hold it any longer, you do it. They go in the corner where the bowl is, with a coat or a blanket to hide them so that they are not embarrassed. It is very warm, it is summer. The second part of July. When I say that it is closed, it is not totally closed, because in a corner, high up, there is some space which lets in a little light and a little air, [about the size] I can let through my hands. There are no railings, not even a child could escape. And where we need to relieve ourselves will become full, it will overflow. You can imagine the embarrassment. And through the small opening, people write words and throw bits of paper. They write words then throw them.

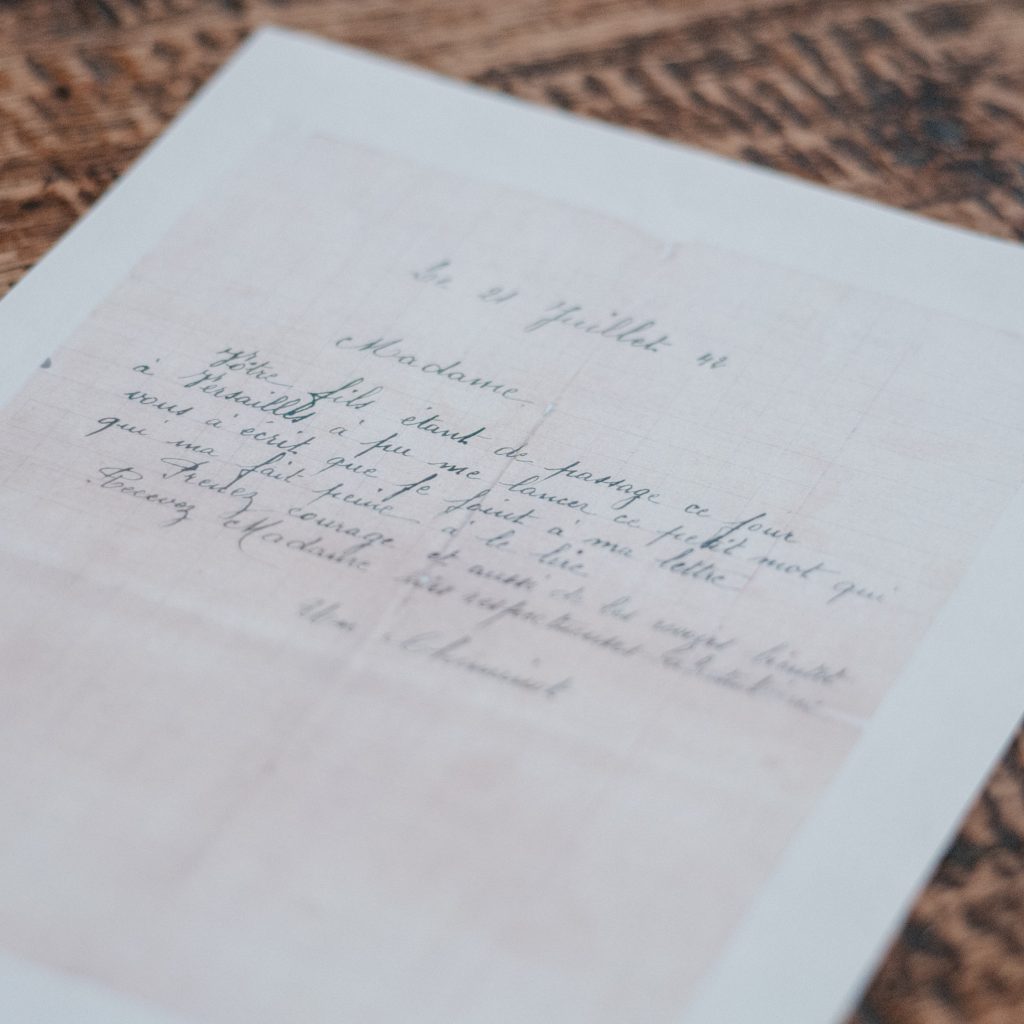

I took a small notebook, as big as my hand, tore a page and wrote a few words for my mother. I put a coin in the middle and folded the paper. I had a small rubber band in my pocket to hold all this together because when I saw people throwing papers I thought that perhaps they would fly away. If I put some metal, some money in it, it would fall downwards and if somebody finds it, that would pay for the stamp on the letter. My mother did receive it – the people working on the railway lines, the cheminots who cleaned and maintained the rail tracks, they picked up the notes and sent them. My mother received my note in which I wrote that it looked as if we were on our way to Ukraine for the harvest. I don’t know whether it was the Germans who said this, or somebody else because we were in July, so I wrote that and later I learned that others had said the same.

It lasted three days and three nights. We didn’t know where we were going. We were in a rush to arrive. We saw that we were crossing France, we could look through gaps or through the small opening at the top. We saw stations with French names, then they were German names. The next day and the day after, they were names we did not know. We were in Poland.

And when eventually the train stopped, it was a relief. We said that to work would be alright – better than being here without food or drink. It was very hot and [we’d] be able to live like human beings, not to be forced to relieve ourselves where it was overflowing.

I was in a corner with my father and brother and I knew my sister was with the other women in another wagon. We understood we had arrived, but there was no station. We didn’t know where we were; there was no platform. You know how, when trains arrive, there are platforms? One leaves the carriage, one sets a foot on the ground. But there were no platforms, it was high and, as we hadn’t walked for three days, people were clumsy, holding luggage – a suitcase, a bag – and having to descend. People were clumsy, they fell and, as it had been raining, it was muddy. It was not a station, it was nothing. It was the end of the rails, a field.

We were so relieved when the wagons were opened, but then we heard shouts. There were dogs, SS, soldiers holding the dogs and carrying guns, and the dogs were threatening us. There were shouts, orders given in a language we did not understand, in German, and we were beaten with sticks. We had been so relieved to arrive and they were shouting and the dogs, they snapped… it was terrifying. We did not understand the orders and they beat us with the sticks. Some understood and were reacting immediately. “What are they saying?” “They say we cannot keep the luggage. We must throw them on the ground, let them go.” For the women, the same, but the women, with their bags… Can you imagine a woman throwing her bag? With photos of children, with her papers, her jewels? The women must have surely taken everything that held value for them.

It was hell because on top of the beatings with sticks, we were frightened of the dogs and we did not understand. “What is he saying?” “He says we must run to the front of the train and raise our hands.” At the front of the train there are SS officers facing us and, as we learned later, there was always a doctor among the officers making the selection.

The word selection? Do you understand? The good ones. The bad ones. And the bad ones are the small children, they are the elderly walking with a cane, they are the sick ones, they are the women holding a child in their arms. But they were not separated, unlike those that came later, but for us it was the start. They had not yet arrested the babies and the very old, we were between 15 and 50 years old. There were some exceptions because there were old parents who wanted to stay with their children, because they thought the children would continue to take care of the elderly.

I am saying all this because it [describes] the arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau. It was how I am describing it. For all those convoys that came later, there were lorries waiting. Women with their babies were sent towards the lorries. If they were holding children by the hand, they were not separated. The young men, the young women have to go to the left.

And the lorries, they drove away, I do not know where and once everything is over, we have nothing left. All our things have been thrown away. Then we walk. We walked one or two kilometres towards the men’s camp. And the women, they go to the women’s camp. We enter into the men’s camp, and to a large barrack.

I do not remember but we were in a large hall and we were ordered to strip naked. It is difficult when one is not used to do it. You can take your the top, but to take off your trousers, it’s hard. Those who do not do it are beaten.

I was 15 years old. I was shy, I was modest. I had to undress – a tragic moment. After six months, it does not matter any more. One gets used to it, one thinks of something else. It is not a problem, it does not hurt. One has got used to it. But the first time, it is terrible.

We saw men in costumes. We call them striped pyjamas, convict clothes. We are given this type of clothes – dirty, used, torn, lukewarm [from delousing]. There are lots of lice, passing on an illness which is contagious, typhus.

Typhus is frightening, even for those in command because they can catch it, and if they do, it’s an epidemic. So they pass [the clothes] through heat and steam, warm enough to kill lice but not [sufficient] to wash them.

The clothes are not clean and perhaps the last ones to wear them had been sick, had dysentery.

It’s the type of illness where you need to run to the toilet when you’re allowed to, and if it’s not free, it’s very complicated. One has to wear the clothes of others who have probably died in them. Deportees come, they clip our hair, shave hair with clippers, moustaches, beards, pubic area, make us take certain position to check we are not hiding anything.

All that happens on the first day. I see my father ordered to undress, bare naked. Never have I seen him naked. Here he is, amid other people. His hair is short, mine and my brother’s too. I have no body hair because I am 15, but they still use the razor everywhere. On the pubic area.

That’s it, all this on the very first day. We have just arrived. We believed we were going to work, perhaps in agriculture, in the fields, in factories, but it’s not that. It is something else.

I am no longer Henri Borlant. I am, what you see here, number [Henri speaks in German] 51055.

Those giving the orders are sometimes Polish. There were Russians and Ukrainians in the camp when I arrived. And for each one it is something different: for the Germans, for the Poles, for the Russians or the Ukrainians.

It’s very complicated. We are scared. We are told, “If you do not answer when we call you, we will kill you.” On our jackets we are obliged to sew a small piece of white cotton on which our number is marked. The number is preceded by a coloured triangle. It depends [on the reason for arrest]. For political prisoners, a red triangle. The killers and rapists who were in prison, they have a green triangle. Those taken out of prison are Germans. There are French and Poles who are not Jewish, who have a red triangle with a F or P. For the Germans it’s a D and this is sewn on the jacket and trousers. So when they look at you, they know whether you are Jewish or not, or Polish, French or German.

Political prisoners, assassins, murderers who were in a prison and taken out of prison, they will be the ones giving the orders. The German political prisoners also give the orders. And that’s how it starts, we have to line up and we are taught the orders. Then you need to stand to attention, take off your cap when they call.

We have to line up. We are made to do it a few times then they take one of us away. He didn’t do it well or maybe they don’t like him so he is taken, he is hit, and killed. They tell us that, here, our lives have no value. Here you are in an extermination camp. None of you will get out of here alive, you will get out only through the chimneys of the crematorium ovens. That’s it.

That’s how it starts; it is a shock. We know that we are condemned to die, that life is finished, that we won’t see our country, our family or any of that again, that it’s here we will die. For shoes, we are given rigid soles of wood with canvas on top. To walk we need to shuffle; if we raise a leg, [we lose a shoe], if it’s muddy, the shoe stays in the mud.

And we carry heavy loads. We have to run, we have to run because we are ordered to run. And they hit us. Very soon we all have sores on our feet and they get infected. And that’s it. We are condemned to die here. We are starving.

When we need to go to the toilet, we have to ask. Every day is hell. We are starving. We are hungry during the day, hungry during the night. For those of my age, this is a period of growth. This is how they make us live. We stay together for eight days in the barrack.

In the barrack there are three levels and on each level we are many, perhaps five, six, at times less, at times more. In the beginning I am with my father and my brother on a level – I think in the middle. When we went back with a journalist, I felt I found the spot where I was with my father and my brother in the barrack. I would not have known it was in the middle but as we went into that barrack, I had this reflex.

How many people? I don’t know. Some mention numbers but I believe they don’t know either. There are many of us when the trains arrive. And when I arrived, at the beginning, there were no gas chambers or crematorium ovens yet. They will come later, in the spring of 1943. I arrived in the summer of 1942.

The gas chambers and the crematorium ovens were already built because thousands and thousands arrived. There were days when the Hungarians arrived, perhaps 8,000 or 10,000 would arrive in one day, and they needed to be gassed and killed very quickly. But when I arrived in August, it was death in a traditional way. It meant we were killed with sticks, with a stick to the throat which kills when it is struck, killed with hunger, with disease.

When I arrived, I caught typhus. Typhus with a 40-degree fever. That’s a high fever. We have no legs, but we have to work, to run, to carry loads. After typhus I had dysentery and I was able to endure it. I survived typhus and dysentery.

When there is a roll call lasting hours and one needs to run [to the toilet] because one cannot hold oneself, then it becomes an epidemic. It was madness. One or two years later, when new people arrive and they were frightened, we told them that now it’s nothing, now life is easier. Now the killing is done on arrival.

And here we are. I stayed 28 months in Auschwitz and Birkenau. With the manual work I did, it’s exceptional.

This is what Serge Klarsfeld [the Holocaust activist and Nazi hunter] told me the first time I went back after the war with some students. Serge Klarsfeld, you know the name? It’s him who asked me. I always told my wife that I didn’t want to go back there. The idea of going… I was often asked to, but I said no.

Then, one day, it was him who asked me. He told me, “I would like you to come with me because I am going with students who are the same age as you were then. They are 15 years old and I will be able to tell them that you were 15 years old.” I did not dare to say no.

So I went to the station and the students were there with their teachers. Klarsfeld told them that I was their age when I was arrested in July 1942 and during that year there had been 6,000 aged under 16 deported from France.

Do you understand? 6,000 children like me – at the same time as me? And he told them that of the 6,000, “He [Henri] is the only survivor.” The historian told the students that.

Because the deportations started in June or July, the first convoy leaving France was at the end of March, but it accelerated. This I did not know. I knew my personal history, but the numbers, the names, I did not know.

And when Klarsfeld said this… when you are told that there were 6,000 and that you are the only survivor. It is something that keeps you awake. Something which gives me the duty to speak and why I’m telling you all this. I wrote a book and, before the book was published, the editor told me she had chosen a sentence from the book for the back cover where I am saying what I’ve just told you: one survivor from 6,000.

As it was the historian who had said this, I asked his permission. I told him, “I am writing this. Do you agree that I can say this, that you told me this?” Otherwise I would not have done it, [to risk ] him saying later, “This is not true, I never said this.” It is so inconceivable – 6,000 and only one survivor. And he agreed.

But I also wanted to tell you of my journey. I spent two months, the first two months at Birkenau. It’s where I arrived. I was able to see my father for five or six weeks. From time to time, I could see him; in the evenings we talked. Then I did not see him any more.

When he saw what was happening, he said, “I know I won’t be able to survive for long because I am 54 years old, but you, you are young. And your mother, when I won’t be here any longer, she is going to need you.” My father knew I was always close to my mother. Perhaps it annoyed him; my brother, who was two years older, was more masculine than me.

I was closer to my mother, and surrounded by all my sisters. All this he said to me and then I no longer saw him. For two months in the camp I was always with my brother but one day, I was taken with others and sent to Auschwitz I, three kilometres away. I was separated from my brother and never saw him again. I stayed at Auschwitz, in Block 7, for one year.

I was taken back to Birkenau which had become a huge camp and stayed there for another year. As I said, I never saw my brother again. And I never saw my sister. After 28 months, it was then the end of October 1944.

The Russians were approaching. We were evacuated – not all but many – to Sachsenhausen, approximately 15 kilometres from Berlin; we stayed eight days. After that, [we went] in the same direction to Oranienburg. Sachsenhausen had real barracks but Oranienburg was an aircraft factory.. We stayed there another eight days, then we were dispatched and some were sent far away; I have the feeling it was by alphabetical order. I stayed with a group among which I had friends and we were the last ones to be sent to Buchenwald, 60 kilometres [away].

I stayed there until the arrival of the Americans; I managed to escape with a friend with whom I worked. We escaped during the night and the next day the Americans entered the town. I met a French prisoner of war who worked in a butcher’s shop. He was a French butcher. We met one day when I had been tasked to get food for the SS kitchen.

We were loading and unloading and this French prisoner of war [was walking] around. He was shocked there were other French men. When he walked by I said, “Yes, I’m French.” He said, “Carry the bucket with me.” We pretended we were going into the butcher’s shop while nobody was looking. He asked me where I came from, I said from Paris. He was from Livry-Gargan.

He had already been a prisoner for years. He told me to hold on because the Americans were not far away: “If you can escape, we are seven or eight French prisoners of war here, we will hide you until the end. My boss, the German butcher, is an anti-Nazi, you can trust him.”

So that’s why, during the night, we escaped. We went there and they hid us, got rid of our clothes, and gave us prisoner of war clothing.

We spent the night there and the next day the Americans come through the streets in tanks. For a day, we stayed hidden. One of my friends – he was ten years older than me, clever, he became very, very rich. Back then he was a poor Polish Jew but he became a big industrialist – he said, “You know, on the first day we must not go outside because the soldiers are advancing. Perhaps tomorrow they will go away and we will find ourselves back in the middle of the Germans. That’s no good for us.” So we kept hidden for a whole day. But, at the end of the second day, the Americans were still there so we came out to speak with them, to tell them what I am telling you now, to talk of the Shoah [Holocaust]. We were nervous, we thought we were going to die, and that the world outside knew nothing of the hundreds and thousands of human beings turned into smoke and ashes. And we were saying that the world does not know because nobody is coming to witness it.

We needed to open up, so we started to speak – I do not know whether in German or in French, interrupting each other. We saw they did not believe us because we were saying unbelievable things. When we realised they did not believe us, we understood that we couldn’t speak with them. They had just arrived and we were telling them things they knew nothing about.

We said. “It is not far: three kilometres. We’ll climb the hill, and you will see.” They took us in Jeeps and, when we arrived, the gates were open. The dead were on the roll call ground. Those who were unable to walk had been killed.

We did not need to speak any more. They saw.

They looked. There was a terrible smell; they saw the dead, piled in heaps, rotting for weeks. Previously, a lorry had come to take away the dead. There were no crematorium ovens in that camp; they were taken to Buchenwald to be burned. Once I was made to take the dead in the lorry and unload them there. In the final days, things were chaotic. Lorries were no longer coming so the dead were left to rot.

And when they saw all this, there was no more need for us to talk. They called [their superiors] and a few days later, they came with General Eisenhower, General Bradley and General Patton, as well as war correspondents, photographers and newspaper reporters. They saw it all. Eisenhower said. “Now our boys will know why they are fighting.”

“It was justified.” He said these words. This was the first discovery of the mass murders. It was me and my friend who brought this about. They would have seen anyway but they had not yet seen Buchenwald. This was the first discovery of the horrors.

We were free in that town where the French prisoners of war were. One day, I met Louis Beuvin, the young French butcher who had hidden us with his German boss.

He said, “We have stolen two cars from the Germans, four in a car. Hop in, we’ll go back to France.” They were seven; eight with me. We said goodbye to everybody and we left for France. We didn’t get far because the American military police told us that we weren’t allowed to drive. Only the American Army had the right to drive. They took our cars and took us to this place they were bringing everybody back to, including all the French, all those who needed to go back home to their countries.

We stayed for three days, waiting our turn. And after three days we escaped during the night and left the town. On 16 April, we arrived in a French town on the eastern border at a huge camp. All the people arriving from Germany were here, being [questioned] one by one to check whether they are telling the truth, that they are not killers, or Nazis. Once identified, they are given official repatriation papers.

When it’s my turn they ask for my papers. I have no papers. “No, no. Everybody has papers,” they say. I said “No, I was deported.” They do not know what deportees are. They know of the prisoners of war, of the workers. Me, I was at Auschwitz-Birkenau, at Sachsenhausen, at Oranienburg. “You have a German accent,” they say. I say, “Non. When I speak in German, I’m told I have a French accent.”

“Do you see? Look, I have a number there.” They do not see deportees, they do not exist for them, they are not here for us. They did not even know there were deportees. I got annoyed and told them to ask the prisoners of war, so the prisoners of war came along. They tell them, “You have no idea how these people suffered, we guarantee it.” So they became very kind, made us our papers. They gave each of us a little money and sent messages to alert the families. We heard the loudspeakers: such and such a soldier is informed that his mother will wait for him at the station… and so on.

For me, nothing; they couldn’t find anybody. I had given the address of my mother, and my maternal grandparents. I did not know my grandparents had been deported the year after I was. Then my French friend, the butcher, comes and tells them. “I’ll take the kid with me. If you do find anyone in his family, call me; here is my telephone number and address.” They agreed and I left with him. We arrived at the Gare de l’Est [in Paris], where his wife was waiting. She looked at me, not understanding why I was there, and he said he would explain.

She drove to Livry-Gargan, close to Paris. His family were waiting for him. He had been absent for five years: this was his homecoming. He had his butcher shop and his flat. His family was around the table waiting for him, for a family meal and they added a plate for me. I think he hadn’t even had time to explain who I was when the telephone rang while we were eating. He came back saying, “They have found your mother, she’s in Paris, in your apartment in the 13th arrondissement. She is waiting with your brothers and sisters for you.” We didn’t finish the meal.

He asked his wife if there were food restrictions. You needed ration coupons, and he asked whether he could give me some meat. His wife answered, “You are the boss, you are the one who decides.” For the first time he put his apron back on, took a knife and asked “How many are you?” He cut a steak for each of us.

There were rations. You couldn’t buy what you wanted and you needed coupons. But here I was in the butcher’s shop. He cut the meat.

They called a taxi and I went home. I found my mother and my brothers and sisters. The caretaker [of the apartments] had objects on her walls that she had forgotten where she’d stolen them from. They came from Bessarabia. They were my grandmother’s.