Miriam Richter

Smadar Yehiely, daughter of Miriam Richter (1919-2016). Kibbutz Nir David, Israel. 6 December 2017.

I’m what you’d call the second generation and my son is the third generation. What occupies my mind is the big gap between the third generation and the second generation.

I work in education, I teach children. I have a very strong connection, an emotional connection, to the Jewish culture of Eastern Europe. That is where my parents came from. And it is very hard for a third-generation child to feel anything about that culture. It’s not his fault, it’s nobody’s fault. I used to take my students to Poland, on what we called ‘a journey to Poland’. After the Holocaust there was a long process of learning. The person in charge asked me to speak about Jewish culture, stories and poems. I felt very close to this culture.

[I was] a teacher who could feel in the first second whether their pupils were listening to them, and I could feel that these were not listening. I was asked to come back the next year and the year after to talk again, but I felt I could not. It was a feeling of failure.

I have spoken with my son about this and now I understand it’s about human nature. You can’t force people to feel a connection with something that is not a part of them.

I have a very strong connection to this world of my parents, even though they did not speak about it. Perhaps they did speak more than other people but, still, we know just a small amount about this world. I disagreed with Israeli students [going to Poland. But I did it as a teacher, sometimes twice in a year, with other people and once with my family which, of course, was the most important. But I don’t agree with this concept because the concept is to show how awful and terrible the Holocaust was, even though one of the purposes is to show and learn about the Jewish culture. Ask these children if they really feel something about that world and they will probably say, “No, nothing.”

The Nazis destroyed a whole world, a style of life, a culture, a people, a language.

There is an expression, ‘the Jewish book cupboard’, and there are a lot of arguments about the contents of this cupboard. Can it only be filled with the Bible? The Talmud? The religious texts? Or can you put in poetry, which Jews from everywhere in the world wrote, and which doesn’t have a connection to the religion? This is a big issue for the Jews in Israel. But outside Israel, there seems to be no issue about this for Jews. Here it is almost impossible to separate religion and politics.

I remember I asked my father, before he died of cancer, if he would like someone to say Kaddish on his grave. He said, “Absolutely not.” With my mother I didn’t even ask as I knew the answer.

The Jews of Europe spoke Yiddish. When the people came from Europe after the Holocaust, it was a new land. It was a kind of mission to speak Hebrew only and to forget Yiddish, nothing that would remind them of the old world, which seemed weak and poor and only for victims. A lot of people followed these ideas, especially in the kibbutz: education, work – what the kibbutz said, people did.

I did not hear Yiddish when I was a child. It was not common. My parents only spoke Yiddish when they didn’t want me to understand them. My parents were educated people and learned Hebrew in Poland, so it was more natural for them to speak Hebrew. But I know that people here of my parents’ generation had to struggle hard not to speak in Yiddish and some of them naturally spoke it at home. For most of my childhood I had no connection with this language but when I started my MA at university, I chose my thesis to be about the connection with one Jewish author who wrote in Russia and for this I chose to learn Yiddish.

I had to learn this second language. It was a great experience for me. I felt it was the peak of my studies: coming home and understanding my parents better. For example, I mentioned how they would not speak Yiddish but how, from time to time, they would use some expressions. I heard them many times and never understood. But now I did. My mother was a teacher so she helped me every day. I learned three times a week, taking a bus to Jerusalem, which wasn’t easy, and she helped me. I was really happy about that.

I have strong feelings for Yiddish as the language of my parents on a social level, a cultural level but not on a religious level. I do not feel the connection with the religious groups in Jerusalem who speak Yiddish.

My father was born in Czechoslovakia; during the First World War his family had moved there. When he was very young they came back to Poland. He lived in Radomysl, a small town in western Galicia [a region in modern-day Ukraine] that I have visited twice.

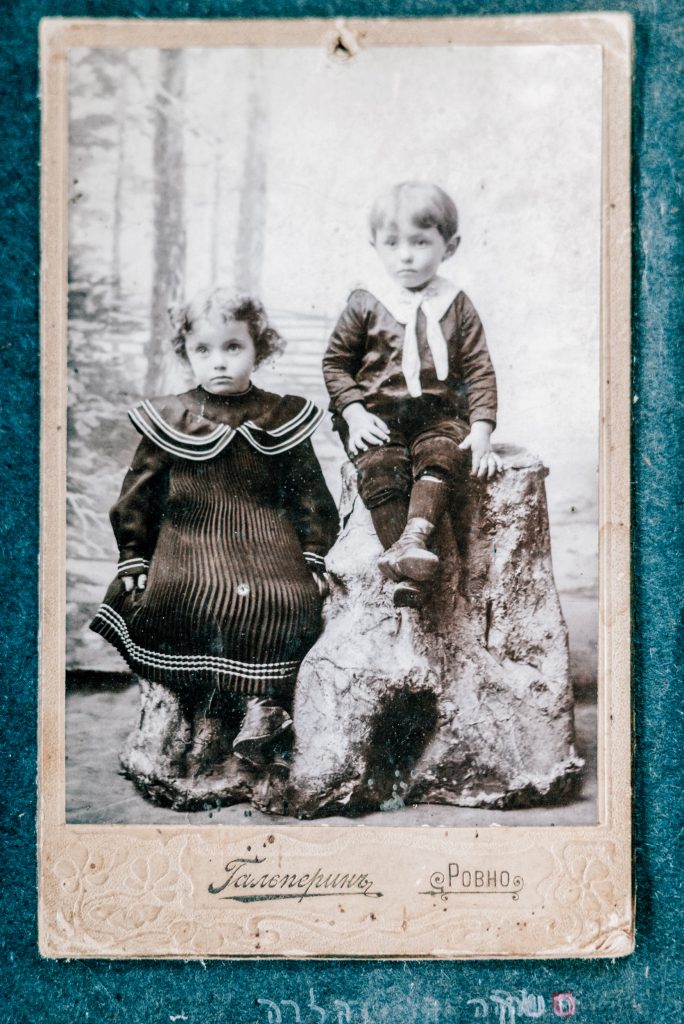

My mother was born in Rovno, a big town in east Poland and which is now in western Ukraine, and now known as Rivne. After the war, it was Russian for many years but then it became part of Ukraine.

We went to visit Rovno, we landed in Kyiv and drove to Rovno. We spent just two days in my mother’s town. We went with my two baby brothers, my mother and me. It was a very strange journey, I was missing my son so much that I wasn’t very focused. I don’t remember much about what we saw. We were lucky because my mother had a good memory and even though she was very old, she was in good shape and could walk. She was not too young when she left and she remembered three houses that her parents moved from, house to house. We went to all those places; the third one was unchanged and we stood outside and looked. We didn’t go inside but walked in the yard which was the closest you could get and, still, part of this journey was made under a fog.

My mother wasn’t very pleased. Later she said we’d hurried and didn’t spend enough time – and she was right. I can’t say I remember anything that stayed with me. I don’t even know where the pictures are that my brother took. He doesn’t know where they are now. I feel that we were very close but we missed something very important. I remember a small trail of things. On the way out of the city we started to go west towards Poland and my father’s town.

Outside the city was a hill and she remembered from here the location of the old Jewish cemetery. So we stopped the car and walked up the hill. It was completely empty, just grass, nothing. I can’t remember why this cemetery doesn’t exist now, whether it was the Germans or the occupying forces. But my mother remembered her grandmother and going to her funeral. She was buried in that place. So we started to walk – it was just grass – and suddenly we saw a few stones that looked very natural but we turned one over and saw Hebrew letters. We understood that we had found what was left of the cemetery. It was amazing. We spent some time there. My brother took pictures. I thought to myself, ‘why is there no operation to save this place, this area?’ If this happened I would go tomorrow. I would pack my suitcase and go tomorrow. This place was very emotional for me, I can’t tell you exactly why. A few hours previously, we were standing in front of the house where she lived. She showed us [where] this and that happened. She showed us a window: “Here, in this window, this is where we boiled the water.”

The most emotional place we visited was Sosenki forest, not far from Rovno. It’s a Russian name: Sosenki. Before the war it was a forest where children went to play. The Germans dug big holes in this place and this is where they killed all the Jews from Rovno – a common way of killing big groups. My mother’s parents and other members of her family were killed here. She knew about it; it wasn’t news to her. We had photographs of this place, we knew exactly where to go, we knew that we would find a memorial. We knew exactly what we were going to find and it took us a few minutes to locate the wall on which her parents names were written – Liza and Zissia Richter We stood there and it was very, very emotional.

It was, in some ways, a way for her to say goodbye to her parents. She started to cry. We had not seen her cry often for her parents in her life. Nor my father. They did not cry, they did not show strong feelings. We could feel it in other ways but not directly. But here she cried, it was very emotional for all of us.

This was the peak of the entire journey because we could feel her tragedy. She had left in 1939 to go to Palestine but, on the border between Poland and Romania, she was caught by Russians and spent two years in a Soviet camp. This is how she survived the Holocaust. It’s part of a very long story of survival but, in this place, she could say goodbye.

My mother, even before she became a teacher, she worked in an archive. All her life she was conscious of writing [things down] so as not to forget anything. She wrote and wrote all her life, about what happened, about small things, about daily life. Because of this we have a lot of material, which allows us to keep the connection between her life and her history and our lives. My son made a film about her and took photographs of her house before we had to pack it up and put everything into boxes.

My father’s was a very emotional story also, but we can’t talk about everything.

— Told by Smadar, Miriam’s daughter