The Feldmann family

Trude Silman (b.1929), daughter of Elsa Feldmann (1899-1945). Leeds, United Kingdom. 31 March 2021.

I was born Gertrude Feldmann in 1929 in Bratislava, which was then the second city of Czechoslovakia. My father, who served in the Austro-Hungarian Army in the First World War, was a banker. Six months after I was born, the Wall Street Crash occurred; he lost his bank and we became rather impoverished. I was never aware of this. My mother’s family were quite well-heeled and supported us. They had a large ironmongery shop opposite our flat. My father kept a little income from journalism and by helping a friend with his estate agency.

As far as I was concerned, I had a normal life. I went to ballet classes and went swimming, and I enjoyed school. I had a happy childhood. I was largely unaware of the rise of Hitler and Nazism until the end of 1938 when my parents sent my older sister, Charlotte, to England. We all missed her, but I didn’t realise at the time that she would never come back home.

The Germans came into Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939. I was sent home from school that day, and I stayed at home and didn’t go out for two weeks. I felt the nervousness in the household. On 28 March, my mother said to me, “Tomorrow morning you will be going to England.” That was the first I knew. My mother packed my things and the following morning a taxi came. I don’t think I understood anything of the politics; all I knew was that the Germans had occupied Czechoslovakia and I had to go away. As a child aged nine, you don’t understand these things. I haven’t any memory of saying goodbye to my parents or brother. I don’t remember whether I hugged them or if we cried. All I remember is a happy childhood, then having to leave. I never saw my parents again.

I travelled to England with Aunt Gita, one of my mother’s sisters, and her four-year-old daughter. The taxi took us to Vienna and then we caught a train. It was quite an eventful journey. It should have only taken 24 hours, but the Germans kept coming on to the trains and taking Jewish passengers off. This happened to us a number of times but we were lucky to be allowed to board other trains. The journey eventually took us four days before we arrived in London on 1 April 1939.

Aunt Gita went ‘into service’ and somehow or other I ended up near Newcastle with a lovely family who had offered to take me in. They were a Methodist family and their church had collected money to put down £50 as a guarantee, which the government demanded, so that I would have enough money to buy a ticket to go home. Of course, that never happened. Although the family were very kind, I didn’t stay long because I couldn’t settle. I couldn’t speak English – I spoke only German, Slovak and a little Hungarian – so it was very difficult. The house was cold, I didn’t like the food and I was frightened of their dog. As you can imagine, I was very homesick and cried most of the time.

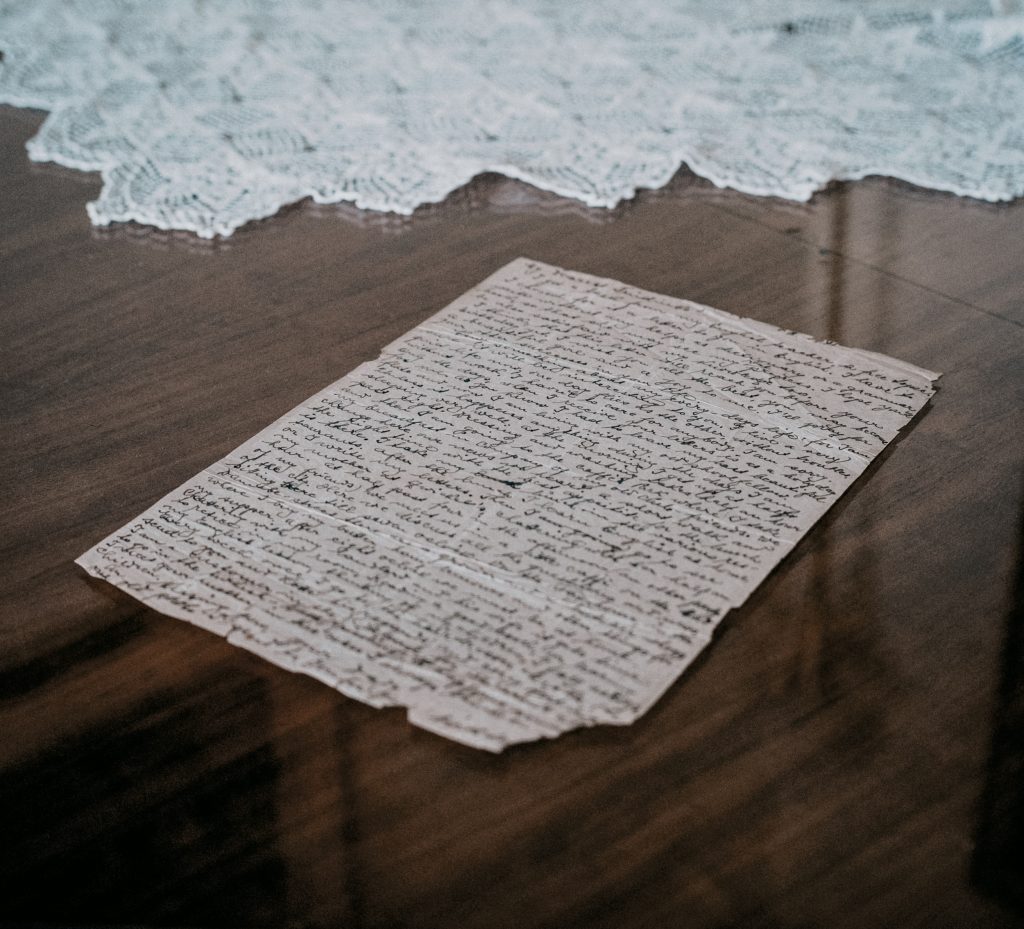

My parents had managed to get all three of their children to the UK, but we were all in different places. My older brother, Paul, came over to England in June 1939. At first, we got quite a few letters from home, but then they became very sporadic. I believe that Father wrote to us every week but we didn’t receive all the letters. When my brother got a letter, he’d send it to me, and I’d send it on to my sister. So, in this way we’d pass letters between us. Father wrote the most beautiful letters to us right until he was transported to Auschwitz in April 1942. He wrote mainly in German, but after his children left for the UK, he learned English so that he could correspond with us in our new language. I received a letter from him for my 12th birthday in April 1941 that was written entirely in English. I have kept this letter as a very treasured possession. I received very few letters from my mother and only four Red Cross postcards containing just 25 words. I don’t know why she didn’t write more. The letters stopped in 1942, after which it was very difficult to find out what had happened to my parents.

After the war ended, my brother received news from Czechoslovakia. A cousin who had survived the concentration camps wrote to Paul in 1945. She had found out that my father had been taken to Auschwitz in 1942 on one of the first transports that had gone from Czechoslovakia. He was killed in the gas chambers within three weeks of arriving there.

I haven’t been able to find out my mother’s fate.

I discovered that in 1942 she married a family friend of her parents, called Ludovit Pasztor. He was 26 years older than her and he had converted from Judaism to Christianity. She got baptised too. They must have thought they would be safer if they were a married Christian couple. Both of them remained free until December 1944, when they were taken to a concentration camp at Sered’, near Bratislava. Within a couple of weeks, my stepfather (whom I never knew) was taken on a transport to Sachsenhausen and was reported dead shortly afterwards. I do not know what happened to my mother after she arrived at Sered’ but I have spent a long time trying to find information.

Initially, I was looking for her with her old surname. I had no idea she had remarried. It was only much later that I found out about her second marriage. I discovered that there were five transports out of the camp at Sered’. Four of them are documented and my mother’s name was not on the lists; but no documentation has been found for the fifth transport. All I can think is that the records were destroyed by the Germans. There was a tiny fragment of paper discovered at Ravensbrück [concentration camp]. It had no name on it, but it exactly described my mother – it had her birth date, it described her working as a nurse, which was true. All the things fitted but the name. I can’t be sure, but I strongly suspect it was her. I think it is most likely that she was on one of the final death marches from the concentration camps. Probably the only women’s death march. About 1500 women started on this march and they were forced to walk 800 km. Most didn’t survive – either shot or dying of starvation, disease or exposure. When the war ended, this march had reached Volary in south-west Czechoslovakia near the borders of Austria and Germany. The cemetery at Volary contains a memorial to all the women on the march, and there are graves for the women known to have died there. I found a gravestone with a name very similar to my mother but, after doing some research, I discovered that it wasn’t her.

So I don’t know what happened to my mother. I am still looking for information and hope that I will eventually find out my mother’s fate. Meanwhile, she remains one of the two million people missing after the war.

Many, many years ago, someone said to me, “You were given a good education and wonderful support – you’ve got to give something back to society.” So, when I retired, I started doing voluntary work. I did all sorts of jobs and roles, mainly related to health and social care, welfare, and public transport. Then one day while I was tidying up my flat, I noticed an advert in a newspaper which said: Are you a Holocaust survivor? We’re making a new group in Leeds, come and see what we’re doing. I’d barely put my nose through the door when I was pounced upon to become the Secretary. I said I’d try it for a month and if I didn’t like it, I’d give it up. To this day, I have never stopped working for the Holocaust Survivors Friendship Association (HSFA).

Initially, the HSFA was a very small group, meeting for friendship and support. We’d share our stories, our childhood experiences, how we’d arrived in the UK, our lives since the war. It was after doing this for a short time that I felt this wasn’t quite enough. I thought, ‘Well, I’ve been a lecturer for all these years – why not spread this further?’ We ought to be telling our stories in schools and to anyone who would listen. We felt that it was vitally important to tell people how easily hatred and intolerance can spread and can result in terrible and tragic events. So, we started an education project. About 20 of us went on a course to teach us how to present our stories, rehearsing what we should say and how we should say it. After a short time, we started speaking in schools, prisons, and colleges. Some of our members who were multilingual would also give talks in Germany, Slovakia and other countries.

When the first Chair of the Holocaust Survivors Friendship Association stepped down, I took over. I was the Chair for many years and eventually I became an Honorary Life President. The next Chair was Lilian Black. She was the driving force in setting up the HSFA’s Holocaust Exhibition and Learning Centre in the University of Huddersfield in 2018. The exhibition tells the stories of 16 Holocaust survivors (including me and Lilian’s father) who settled in Yorkshire. This is the first Holocaust Centre in the north of England. Tragically, Lilian died of Covid-19 in 2020. I hope the centre will go from strength to strength as a fitting legacy to her memory.

I have given talks all over England. When I talk to children, they seem to be very interested. They learn about the Holocaust at school but having an actual survivor tell their own story makes it real. I tell them about my childhood and my school life, and I try to get them to identify with me, to understand that we are all human beings irrespective of nationality, colour, religion or beliefs.

I’ve told my story many times and I hope that this has helped, albeit in a very small way, to increase tolerance and understanding.

I firmly believe that Holocaust education can be a powerful tool to help people to realise that we are all the same under our skin and we all have the same needs and desires. I would like all of the people of the world to realise that, whatever our differences, we should be tolerant and kind. We are all human beings who deserve to be treated well and to have a decent life.

— Written down by Trude Silman