Sylvia Kerner and her family

Sylvia Kerner (b.1941). London, United Kingdom. 7 April 2021

I’m doing this for my three children, Jamie, Stefan and Vanessa, and their families and my grandchildren because they may wonder, one day, where do I come from? Where are my ancestors? English people and others can trace their families so far back; unfortunately in my case I have only have two generations.

Those who died in the camps, there’s no sign anywhere of their existence. They lived, they died. They went up in smoke. There is no grave, no nothing. And, yet, they did exist. They created a family and you, my children and grandchildren, are part of this family; you are the link to the future.

In Paris, there’s the museum of the Jewish memory [Mémorial de la Shoah] and there you’ll see the names of your grandma and her brother. My grandmother was Hélène Zajfman, and, Vanessa, you’re called Hélène after her.

My grandmother had a brother called Nuta, Nathan Zajfman. You, Stefan, you’re named after him. Your grandma, Mémé, was so happy that the memory of her family lived on with you.

My mother, your Mémé, Sabine Zajfman, was born in Warsaw, in July 1904 I think, to Hélène. We don’t know anything about Mémé’s father. They never spoke about him. Mémé’s mother was a dressmaker. They were very, very poor.

Mémé always said that in summer in Poland, it was very hot. They couldn’t afford anything but they used to love buying watermelon; it was cheap and very refreshing. Mémé was a very beautiful young woman and very, very clever; she went on to study biology.

But then the Nazis started entering Poland so my mother, grandma and grandma’s brother decided to leave. They took the train and arrived in Paris. They chose France because my mother knew a bit of French. They found one room for three people, on the Rue de Louvrois.

I was born in 1941. In July 1942, in Paris, the French police started to round up the Jews.

My father was in hospital, he had something wrong with his stomach. They had fake papers, which I’ve still got, and the doctor knew that my father was Jewish. He came and whispered in his ear, “You have to leave. I hear that all over Paris, the German and French police are rounding up the Jews. Whether you can walk, crawl or are on a stretcher, they will take you.”

My father started crying. Next to him was a man called Réné. I suppose he asked, “What’s the matter?” And my father said, “I have to go and hide; I don’t know where. I don’t know how I’m going to do it. But I have a little girl. Her name is Sylvia and she’s one year old. I can hide myself. What can I do with a baby of one?”

This man said to my father, your grandpa, “My sister is going to come and visit me this afternoon, I’ll ask her if she wants your child.”

When I used to tell this story before I had you, I had actually no emotions. I didn’t know what it meant to have a child and then – can you imagine? – give it away. So many people did this so their children survived even if they died.

This lady arrived and I ended up living with the Galiadzi family from 1942 until 1945. They lived in Malakoff, which is now part of Paris. They risked their lives because if somebody had known that they were keeping a Jewish child, they would have been sent to the camps.

I don’t have really any memory of this time because I was a little girl, a baby. I was five when I came back to my parents. The only thing that I do remember is the prayers, Donne-nous aujourd’hui notre pain de ce jour… [Give us this day, our daily bread] so I must have gone to catechism with them. After the war we kept in touch with this family and when Brian and I got married in Paris, Nicolas Galiadzi was our witness and my father made a speech, thanking the family for saving my life.

My parents lived on the fourth floor without a lift and I remember that after the war we came back to this flat and somebody else had taken the flat. It was a Monday, how do I know? On Mondays, people used to do their washing and in those days they used to have a big tin to boil the linen. This woman wouldn’t leave the flat, so the police took the two handles [of the tin] from the fourth floor and put it on the pavement so that my parents could have their flat back.

During the war there was a concierge in this block of flats, and all the Jewish people had to wear the yellow star. This woman wouldn’t let my mother or father without the yellow star.

Before my mother gave me to those people, I remember the police banging on the door. There was my mother, her mother, and me, aged one.

And they took my grandmother; in Yiddish she told her daughter to “look after the child.” They said to my mother, “We will come back to take you in one hour.” Within this hour I suppose my mother… I don’t exactly know what happened.

Even up to the time my mother died, somebody might ask me, “What happened to your parents during the war?” And I just repeated what I had heard for many years until my mother died aged 88. I would say that my mother was a companion to a baroness and that my father lived on a farm, that’s all. That’s all I knew.

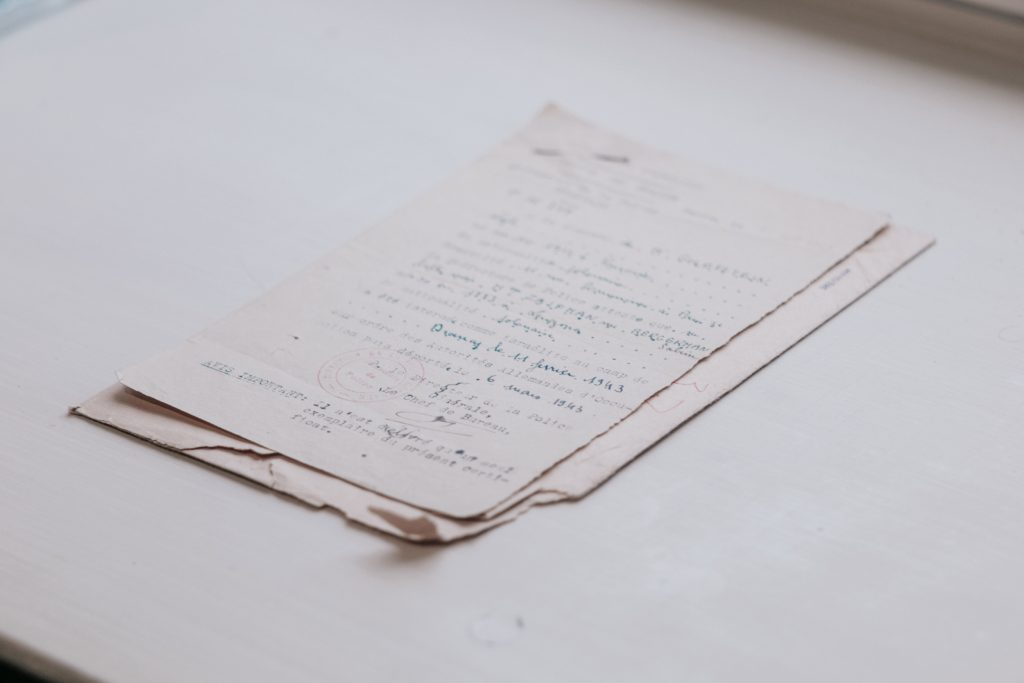

When my mother died, I went to the flat and started looking in drawers. I found a letter written on 1 July 1944. When you touched it, it crumbled, so there are only bits of it left.

I only read it once because I couldn’t read it again. A few months ago some friends were here and Brian [Sylvia’s husband] told me go and get the letter. So I said, “I don’t think I can read it.” Brian said, “Bite your lip and try.”

Then we were at the table. It was a Friday night and we’d invited this couple. I started reading the first two lines. It was impossible for me to read it. I was sobbing and trembling and so I have never read it but here it is in essence.

It was written on 1 July 1944. And that was my mother’s birthday. She writes to her husband, “How are you?” She wondered if she would ever see her mother or brother again, and then she describes her life, which was like that of a slave. But because the woman knew she was Jewish, at any moment she could denounce her and she would be sent to the camp.

A few years ago, Brian and I were in Yad Vashem and they had a computer. I said to Brian, ”Let’s put in my grandmother’s name.” Hélène Zajfman, née Bergerman. Hélène Bergerman was sent to Drancy on 16 July 1942 and in August – I’m not sure of the date – she was sent to Auschwitz on train 302, from platform three, departing 14.01. That’s the last we heard of Mémé’s mother.

Your grandma’s brother is another story They said that all Jews had to report to the police. Pépé and Mémé, my parents, said to him, “Don’t go.” “Why, what have I done? I’m not done anything.” He wouldn’t listen, he went.

I can’t remember exactly how and why but he was sent to Pithiviers, which was like Drancy: a camp before they were sent to the death chamber and the gas chamber. And he sculpted and sent a pen holder with his picture in it in wood, which I had framed. It says, ‘To my darling sister.’ It’s on the wall as a memory.

And Mémé… all those years until she died… We always said that he died in Pithiviers of typhoid because illnesses were raging in the camp. There was no hygiene and no medicine. But one day Vanessa and I… Darling Vanessa, do you remember we were playing with Google? Is that the word? Playing? Can you remember, darling, you typed Nathan Zajfman? And in brackets it said ‘Nuta’– which is the Yiddish. ‘Died in Auschwitz.’ This was contrary to the general understanding that he died in Pithiviers.

Those two people had, I imagine, the most terrible, terrible journey. In a cattle truck with no hygiene, no food, no air. Half dead before they had to walk the last steps to the gas chamber and leave this earth in smoke. I’m doing this because these people existed. They had a heart, had love. They were loved. They didn’t want anything except to have a family but because they were Jewish they had to die.

After me, my parents had two children but they died. A little boy called Bruno; in 1946, I think. He died at eight months old. The doctor said there was nothing to be done so they took the child home and he died at home in that flat. How awful it must have been for my parents.

My mother was pregnant when he died so, I suppose you say, ‘I know it’s horrible to lose a child and nothing is worse than that, but thank God she’s pregnant.’ But then that little girl, Rosine, she died at five days old.

I have a recollection of my father hiding me under his coat to see the newborn baby because, I suppose, children weren’t allowed to see newborns in those days. And that child died. She had a hole in the heart.

My father, people tell me, never really recovered from losing two children after the war, having suffered so much, having hope for a better future. They lost two children in one year.

I go each year to the cemetery to see the names there on the tomb. And on that tomb there’s also a picture of my mother’s mother and her brother. There is no body of course, but there’s a memory there. They are there, on the tomb.

We were very modest people. My father was a tailor, not in a big way. He used to make raincoats and uniforms for Air France pilots. I didn’t fancy going to university. I was a very good linguist and I loved travelling. When I was 18, I had my first boyfriend. He was 10 years older than me because I was always quite mature and always liked older people.

When you were 18 or 20 in 1960, it was difficult to find a boyfriend because all the children that would have been born in 1940 or earlier would have been aged around 5 or 10 [during the war]. Jewish children were killed. So in 1960 there were not many Jewish children of 18 or 20.

Two people I know who were in the camp and were survivors and had numbers on their arms, they reacted differently. My mother had a cousin, Marcel. I loved him. Marcel was very serious about it and carried the memory of it. He talked about the Vel D’Hiv [Vélodrome d’Hiver, site of a mass roundup] which obviously doesn’t exist anymore. Now there’s a plaque where the Vel D’Hiv was, and every year the numbers are dwindling.

And he and his wife were consciously keeping the memory of this terrible event. Simon, on the other hand, coped with his nightmare with humour: “When I was in the camp, I was lucky. Why? I was warm. Why? I was burning the corpses and that kept me alive. I didn’t freeze to death. I was warm.”

You can’t criticise this reaction because you weren’t there. Another thing: when people say, “Can you forgive?” You can’t forget and you can’t forgive an unforgivable action.

When I went to Auschwitz with Brian, he told me to take Marcel’s and Simon’s phone numbers but I didn’t take them. But when I was there I wanted to speak to them. Again, two different reactions. I phoned Marcel and said, “I’m in Auschwitz, I’m thinking of you.”

He had a brother. They were 17 and 14, these two boys. One of the guards was beating Marcel’s brother with the cross of his gun. The poor fellow was dying on the floor. Marcel was obliged to watch and the guard said to him, “Here’s my gun, finish your brother.”

When you hear these horrific stories of torture, when it’s brought to you so vividly, it’s a terrible thing. Marcel obviously couldn’t do that. But [the guard] said, “You are saved,” because they rang the bell for lunch and Marcel took his brother in his arms. He put him on a wooden bench and the poor fellow died.

Then I phoned Simon. I told him I was thinking of him. He said “I was in building number 10 and number 11 was a bordello.” This was where the guards used to rape the Jewish women.

My youth was really enveloped in the Holocaust because my parents’ friends suffered. When they gathered together, you could be sure that within half an hour the subject would be what happened to them in the Holocaust.

You were part of the Jewish people who perished, who were taken, who were taken to the Vel D’Hiv, to Drancy, onto the train, who ended up in smoke. Your spirit died. You are here but some [part] of you is dead.

We talk about six million Jews, the victims of Nazism, but I say that there were many more. Me, I am a victim of the Holocaust. Even now after more than 60 years, I still cry. And I still don’t understand how it happened. Why? How did the world let it happen?

And still that hate, that hate in the world for the Jew, I don’t understand why. It’s a mystery to me when the Jews – as a nation, as a people – have done so much for the world.

I want to tell my grandchildren, whether they live a Jewish life, whether or not they marry a non-Jew, they have Jewish roots and these Jewish roots died because of the most terrible, terrible ideology which considered Jews worse than vermin. And yet, with this terrible history, people are still telling everybody, that the Jews are less than human and they want to kill us.

Whether you live a Jewish life, you have to think of your Jewish roots. When you have children, you must tell them that there’s Jewish in their blood whether they want it or not [Imagine] if Hitler was still here: whether your children are Jewish, or if they had Jewish grandparents, or great-grandparents, they would end up in smoke. You must never ever forget it.

— Told by Sylvia to her children and grandchildren