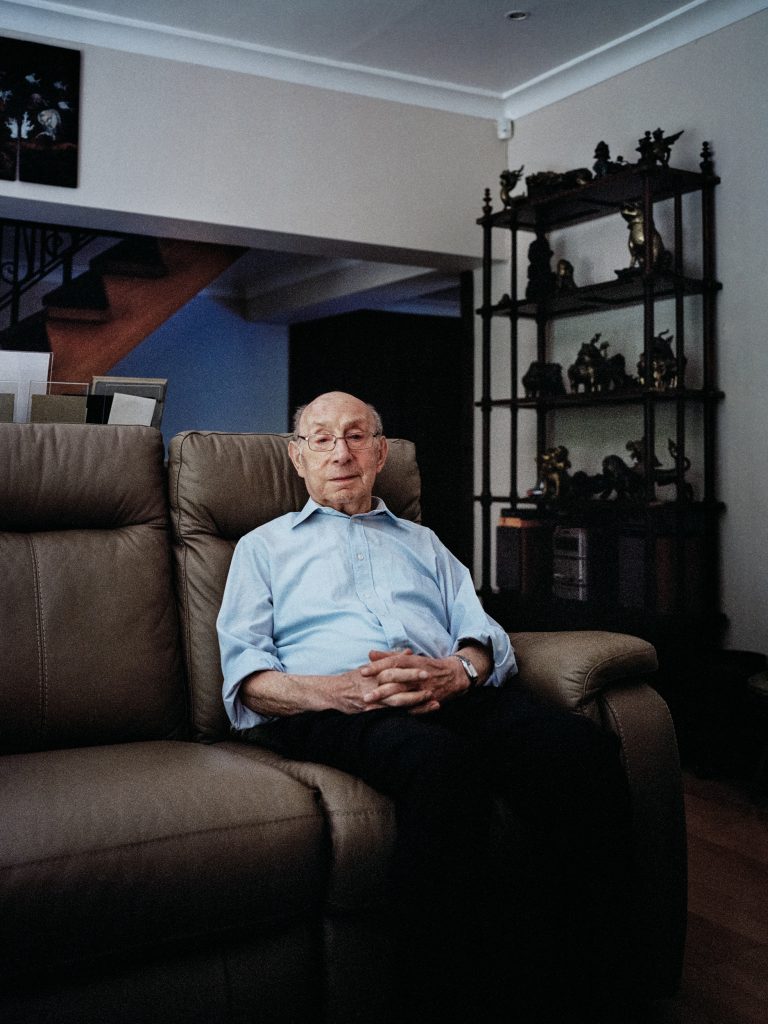

Harry Mans

Harry Mans (1933-2020). London, United Kingdom. 26 July 2018.

I was born in Amsterdam on 1 October 1933. At that time my parents lived along the Keizersgracht, one of Amsterdam’s many canals. They had fled from Poland in the 1920s to escape the many pogroms at that time. They got married in Holland but, when I was still very young, they divorced. I don’t know exactly when or for what reason, as my mother would never talk about it. My parents remained friends however, and my father, who had moved to The Hague, came to visit us most weekends. At that time it was very difficult for foreigners to find work in Holland, especially for people like my father who had no particular skills or education. He took whatever job he could find and worked as a market trader and a waiter among other jobs; my mother, who was a very good seamstress, managed to find work more easily. Life was very hard for them and ours was very much a hand-to-mouth existence.

After my grandfather died we could no longer afford to stay in the flat on the Keizersgracht, so we moved to Meerhuizenplein, a small square in a rather poor part of Amsterdam. There, my mother and I shared a flat with the Halperns, a German-Jewish family who had fled Germany not long after Hitler came to power.

When they left, my mother and I could no longer afford to stay in the flat. This time we moved in with my grandmother, [her husband] Maurits and Tieneke [Maurits’s daughter]. It was a small flat, not really large enough for two families, but we managed, for a while at least.

Hitler had appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart, a Viennese lawyer and ardent Nazi, as Reichskommissar in the Netherlands. At first he promised not to interfere with Dutch institutions such as law, education, the civil service etc. However, that promise was soon broken and the Nazis started imposing their own political philosophy on the country. The most important and urgent part of this philosophy was, as we now know, the total annihilation of the Jews of Europe. In this respect they were very successful in Holland, which had a Jewish population of about 140,000. Quite a few of these were people who had escaped from Germany, and later from Austria, in the hope of finding safe refuge in Holland.

Unfortunately it didn’t work out that way. Of those 140,000 Jews, about 30,000 managed to go into hiding. The remaining 110,000 were deported, mainly to Auschwitz and Sobibór; of these only about 6,000 survived. Three quarters of the Dutch-Jewish population perished. This is a much higher percentage than in any other West European country. There were many Dutch people who risked their lives to help the Jews by hiding them. This was difficult as Holland is a small country with no large forests and no mountainous terrain.

There were a lot of collaborators and informers, some of whom acted as bounty hunters. They were paid a sum for each Jew they turned in. There were also about 25,000 young Dutchmen who joined the Waffen SS. Many were sent to Russia to fight and never came back.

Gradually all sort of restrictions were imposed on Jews. We were no longer allowed to go to cinemas, theatres, restaurants or clubs, or even to sit on park benches. Jews were not allowed to own cars or travel on public transport without a permit and were not allowed to have telephones. Jews were dismissed from the Civil Service and Jewish doctors were no longer allowed to treat non-Jewish patients. We then found out to our horror that our GP, a German refugee, had poisoned his family and himself rather than suffer at the hands of the Nazis.

Jews were forced to deposit all financial assets such as bank accounts, insurance policies and share certificates with the special Jewish bank of Lippmann, Rosenthal & Co. The Nazis had full control over this bank and when clients were deported they seized their assets and sent them to Germany. This did not affect my family as we didn’t have any assets.

In the following winter of 1941-1942, which was very cold, Jews were no longer allowed on the ice and we could only stand at the river’s edge and watch other kids enjoying themselves. There were notices all along the river which read Voor Joden Verboden [Forbidden for Jews]. These also appeared outside the other establishments and parks where Jews were not allowed.

The Germans even went as far as changing the names of streets named after Jews. For example, there was the Dutch-Jewish painter Joseph Israels, whose paintings were so highly thought of in Holland that a street which ran along the Amstel was named after him. The Germans changed the name of that street.

The next thing I remember is that all Jews who were old enough to have to carry an identity card had to register and have a large letter J stamped on the front of it, near their photograph. This didn’t apply to me as I was not yet old enough to have an identity card. Then, in May 1942, all Jews over the age of six had to wear a yellow Star of David made of cloth and which had the word JOOD [Jew] printed in large black letters in the middle of it. This had to be worn on the left-hand side of all outer garments. As I was eight years old by then, I too had to wear one. We had to buy these stars at a cost of four cents each and they had to be sewn on with the stitches so close together that you could not push a pencil between them. The wearing of the yellow star made us, of course, easily distinguishable. So now the Germans could really go to town. They started by imposing a curfew on Jews. We had to be indoors by 8pm and were only allowed to do our shopping between 3 and 5pm. This made life difficult for people like my mother, who was at work between those hours, but luckily for us my grandmother who did not go out to work, could do most of our shopping.

At that time I was going to an ordinary infant school about a 15-minute walk from my home. In the school there was no such thing as assembly for prayers. It was a secular school and, as far as I remember, religion was never mentioned. Our teacher was a very nice woman and I also got on well with my school friends, most of whom were not Jewish. The Germans however decided to change all that. They did not allow Jews to mix with non-Jews and, as this even applied to children, they forced our school to become a Jewish school. All the non-Jewish teachers and children were sent to other schools and Jewish teachers and children from other schools were sent to ours. We were naturally all upset at losing our teacher and most of our friends. Our new teacher, like our former teacher, was also a very nice and caring woman. She and her husband even came to visit me at home once when I was ill. I cannot remember her name, so I have no way of finding out if she survived the war. Every so often one or more of the children would not turn up at school. This almost always meant that they and their family had been arrested in the night during a razzia (raid) and would probably never be seen again. The Germans usually carried out their razzias at night so as not to upset the non-Jewish population. My best friend Arie van Hoorn and his parents were arrested during the night. We lived at number 7 Marcusstraat and Arie lived at 19. As I passed his home on the way to school I always used to call for him. One morning I rang the bell but there was no reply and I never saw him again. Only fairly recently did I discover that he and his parents had been gassed in Auschwitz. He was eight years old.

Next came my father’s turn. He lived at number 2 Amptstraat, Scheveningen. In that house there also lived two couples, each with one child, and there was also one young woman who lived alone. None of them survived the war. Like my Aunt Bronia and her family, my father also received a summons at the beginning of August telling him to report to the railway station in The Hague at a specified time and to bring a change of clothes and other necessities. Again, family and friends told him not to go, but to go into hiding instead, but he wouldn’t listen. There was no need for him to go, because his appearance was such that nobody would ever have suspected that he was Jewish.

My mother and I went to The Hague the day he had to leave and spent the night there. When I went to bed we said goodnight and that was the last time I saw him. He was first sent to Vught transit camp, from where we received two postcards from him during the first week. After that we heard nothing more and it was not until some time after the end of the war and several enquiries, that the Red Cross informed us that he had been murdered in Auschwitz on 21 September 1942. He was 36 years old.

The Germans had set up an organisation called the Jewish Counsel which was made up of Jews who were forced to organise their own people for deportation. One of the things they had to tell us to do was to have a rucksack or small suitcase ready packed with essentials at all times, which we did. This was obviously done so as not to keep the Germans or NSB [Fascist Party] members, who were Dutch collaborators, waiting when they came to arrest us. I still have my rucksack, now over 70 years old.

The window of our bedroom in the Kan’s flat faced the street and one evening we saw two black-uniformed members of the NSB take my grandmother away. They took her and not Maurits because she was not a Dutch national whereas he was. He was looking after his daughter who was only half Jewish. It was terrible to see my grandmother taken away with her rucksack on her back, not knowing where they were taking her and completely helpless to do anything about it. She was taken to the Hollandsche Schouwburg theatre which was used as a registration centre. The Germans were very meticulous about taking details and keeping records of their victims.

Now came our turn. One night, I think it was a Thursday, at about 2.30 in the morning we were woken up by a knock on our bedroom door. It was Mrs. Beek to tell us that we had to get dressed because there was a razzia and the German police had come to arrest us. They had come for the Beeks and had then asked them if there was anyone else in the flat. They had to tell the Germans that we were there otherwise the consequences could have been very serious for them. We got dressed, put our ready packed rucksacks on our backs and went downstairs to be met by two members of the German Gruhne Polizei. This means green police, because of their bright green uniforms. They took us and several other Jews they had arrested to a small square at the end of Apollolaan where there were two or three lorries waiting. As soon as the lorries were full they drove off. As it was about the beginning of February, it was bitterly cold. We didn’t know at that stage where we were being taken, as we were not yet aware of the fact that all Amsterdam’s Jews were taken to the Hollandsche Schouwburg theatre for registration before being sent to either the Vught or Westerbork transit camps.

When we arrived at the theatre, we were lined up on the stage and directed to what looked like a row of trestle tables behind which were seated members of the Jewish Counsel who took everyone’s details. I have no recollection of the man who dealt with us. I never knew his name, – call him Mr. X – and cannot remember what he looked like or what was said. After taking our details he told us to go and take a seat in the auditorium. The auditorium was quite crowded and we were told that some people had been there for three weeks, living on bread and jam. Mr. X came to see us twice during the night and at about 10am he came again and told us to pick up our rucksacks and follow him, which we did. He took us along one of the aisles towards the back of the theatre, then along some passageways to a door which turned out to be a rear exit door. He then opened this door and told us to go. There wasn’t even a German guard at that door. We didn’t need to be told twice to go, so we rushed back to my grandmother’s flat.

The first thing my mother did then was to go to see Mr. Hageman, our non-Jewish neighbour who lived on the ground floor. She told him what had happened and asked him if she could use his phone to ring my Aunt Poldi. When Poldi heard what had happened, she immediately said that it was much too dangerous to stay where we were and she told my mother to pack a couple of suitcases with all necessities and that she would collect us the following day. She also told us not to go back to Apollolaan as the Germans would almost certainly come looking for us. Although Mr. X saved our lives, the sad part of this event, which my mother did not tell me about until I was in my late teens, was that the same evening of our escape Mr. X came to see my mother in Marcusstraat and wanted his reward in the form of sexual favours. My mother told him that he should be thoroughly ashamed of himself, especially given the circumstances and she sent him packing. If Mr. X had wanted to take his revenge by telling the Germans where we were, he would obviously have implicated himself in our escape. In any case, they would have drawn a blank because my Aunt Poldi came to collect us early the following day. We had, of course, removed the yellow stars from our garments. And so began our very lucky escape from the Nazis and almost certain death. I was nine years old at the time. A short time after we had gone into hiding my grandmother was arrested for a third time, but this time she was not released. She was sent to Sobibór where she was gassed in June 1943 aged 56.

After spending about two weeks in Blaricum, Aunt Poldi found a hiding place for my mother. We had to split up as there were very few families who were able give shelter to more than one person. Most families preferred to shelter children as these were less conspicuous and their presence easier to explain. I was not told the location of my mother’s hiding place in case I was caught and questioned.

A few days after my mother left, Aunt Poldi also found me a hiding place. This was in a lovely village, not very far from Blaricum, called Laren. I slept on the first floor which was also the loft and my bed was just under the skylight. The main bedroom where Sientje and the baby slept was on the same level. One night there was a terribly loud aircraft noise which woke me up. When I opened my eyes I saw that the whole attic was illuminated through the skylight as if it were bright daylight. The Germans had shot down a British bomber which crashed in a field in Eemnes, a village not very far from Laren. We later learned that at least some of the crew bailed out and survived.

The Wikkerman’s home occupied the front half of a corner house which had a thatched roof. The other half of the house was occupied by the Calis family who were sheltering a little Jewish girl about four years old. I used to push her on her swing in the garden. I don’t know what happened to her. These families were religious Roman Catholics and went to church very frequently. No-one ever asked me where I came from or about my parents. The fictitious story I had to tell if I were ever questioned was that I came from Rotterdam, a city I had never yet been to, that my name was Hans van der Vecht and that the address was 236 Schiedammer Plaats, Rotterdam. This street had been bombed and completely destroyed during the air raid in May 1940. The rest of the story was that my mother had been killed in that air raid and that my father was working in a factory in Germany. He was in fact dead by then.

Unfortunately I had to leave Sientje’s house where I had been quite happy, if somewhat undernourished. The next hiding place I was taken to, in the village of Huizen, was still in the same area called Het Gooi. Again, I was very lucky to end up being sheltered by such a nice family. They were the Vierhouts and consisted of Mr and Mrs Vierhout, their daughter Mieke, aged 14, and their son Fred, aged 11. I only saw Mr Vierhout two or three times, as he was also hiding from the Germans in another location. The road where this family lived was called Paviljoenweg. It was a short cul-de-sac at the end of which was some woodland where I used to take their little black dog for walks.

This next hiding place was a large house in Naarden, again in the same area, Het Gooi. It stood in its own grounds and set back quite a distance from the road. The woman who lived there was obviously quite well off. She must have been in her early thirties and she had a live-in maid. From what I gathered from their conversations, my hostess was expecting a baby. This was probably another case of the husband, who I never saw, being in hiding somewhere else to avoid being sent to Germany. I never got to know her name and, quite frankly, I don’t want to know it. She was a hard-faced woman and very unfriendly. She obviously resented me and I shall never understand why she took me in or why she resented me.

The terraced house in Delft, where I only stayed for two days, was in a street which ran along either a river or a canal. The only thing I know about the family is that the man was a lawyer, a prosecutor to be exact, because when I arrived at the house it was dark but I could see a brass plate by the door with the name Cherdon and the title Procureur. There were two other Jewish children in hiding there as well as a young Jewish nurse called Willie. We were on the second floor and we children only saw Mrs Cherdon on about two occasions. Willie was the only one who used to go downstairs and get food for us all and she really looked after us. After a two-day stay, all of us were taken separately to other destinations, each accompanied by different members of the resistance.

The place where I was taken to was a water tower in Brunssum, a small town in the southern province of Limburg, very close to the German border. The water tower was a water pumping station which pumped water to the only coal mine in Holland. It was located near Brunssum and the coal mined there was, of course, requisitioned by the Germans who needed it for their war effort.

We finally arrived at the water tower in the evening and, as it was winter, it was dark and very cold, so I could not see what the place looked like from the outside. I had to go up several flights of stairs inside the tower until we reached the floor just below the top. There, I was taken to a room full of children about my age. We were 12 children altogether and there were also two Jewish men in about their thirties. To my surprise, Willie the nurse was also in the room. She must have been taken to Brunssum via a shorter route. In any case, I was very happy to see her.

There was a second room on this floor where the two men slept and where, during the day, all the mattresses were stored. These mattresses would be taken to the children’s room in the evening and laid out for sleeping and then returned to the other room in the morning. Willie slept in the room with us children. It was impressed on us every day that we had to be very quiet at all times as there could always be German soldiers wandering around.

With so many people in one room most of the day and all night, the standard of hygiene was poor to say the least. Willie did her best to keep us clean and also saw to it that our clothing was laundered, but in spite of her efforts we were plagued by fleas and head lice. Almost all the children caught colds from one another, but luckily there was no serious illness. We had enough food and, unbeknown to us at the time, a lot of this was provided and prepared by some of the people of Brunssum who also did many other things for us, including the laundry. The two men used to entertain us by telling and reading stories and we also played board games. The atmosphere in the place was generally very good. There was a feeling of togetherness, no doubt because we must have sensed that we were all in the same boat. There was very little in the way of squabbling or disagreements.

Jaap Musch [founder of the Dutch resistance group NV] sometimes came to spend a night with us in the tower. This was probably when he was on one of his missions. From time to time, when it was a dark evening, Willie used to divide us into two groups and take us out for a walk in the surrounding countryside, sticking mainly to the woodland. Each group was taken out on a different evening. It was midwinter and very cold. When walking, we could hear the ice cracking under our feet. Speaking or even whispering was not allowed. These were the only occasions when we got some fresh air. We were not allowed to open the windows; they had to be kept shut to keep in noise and warmth.

Two of the boys who had come from orthodox families used to go out on the landing on the floor below at a certain time of the day with a prayer book and say their prayers.

After about six weeks in the tower, it was time to move on again. It was very early 1944 and I was ten years old. Another train journey accompanied by Ted, this time to Leerdam, a small town in the province of Zuid Holland [South Holland]. I had never heard of this town and apparently the only thing it was known for in Holland was its glass factory. Although I didn’t know it at the time, this was going to be my last hiding place before the end of the war. It also turned out to be my happiest.

I remember immediately feeling at easy with Adrie and Mees and asking them if I was going to stay with them, or if I had to move on again. They assured me that I would be staying for a while. Much later Mees and Adrie told me that when they first set eyes on me they thought I looked like a hunted animal. They later also told me that if anything had happened to my family they would have adopted me.

The first thing Adrie did was to go and buy me some new pyjamas, underwear and shirts because by then mine were in a terrible state. Mees and Adrie had no children of their own; apparently Adrie could not have any.

In August 1944, Mees and Adrie were asked by the resistance if they could shelter a man called Leen Hartog. Serving in the Dutch navy, he had been taken prisoner and managed to escape. He had been in several hiding places and had finally managed to get hold of false documents. One gave him the false name of Leendert Bakker and stated that he was doing some work for the Germans. The other document stated that under no circumstances was his bicycle to be taken from him because he needed it for his fictitious work. I have a book with photographs of these documents. Mees and Adrie immediately agreed to take him in and he and I ended up sharing the bedroom in the loft.

We were now approaching the end of the war and the food situation became dire. We had eaten the two rabbits and now lived on the little fish we managed to catch and any vegetables we could find. Our bread ration was almost non-existent and of such poor quality that it wasn’t worth eating. It contained all sorts of ingredients, including sawdust, and its consistency and taste were most unappetising. However, we were lucky not to be living in a large town such as Amsterdam, Utrecht or The Hague, where several thousand people died of starvation. Mees and I went on his bike in search of food. I remember he had a new blue overall which he managed to swap at a farm for potatoes. We made a few outings like that.

The Allies were just south of the River Waal and could have crossed and liberated us, but the Germans threatened to blow up the dykes and flood the land if they crossed. As a lot of the land was below sea level this would have caused a tremendous amount of damage.

After the euphoria of the liberation had subsided, life improved in that we had more food and life seemed more relaxed for my foster parents. We didn’t know where my mother was or even if she had survived the war. Then one afternoon, about three weeks later, a small car pulled up outside the house. Two men got out and came to the house. One was a Mr Troeder, who had been a Jewish member of the resistance, and the other was a colleague of his. They told my foster parents that my mother was alive and living in Laren and that they had come to take me back to her.

Mr Troeder could not have informed them of this in advance, as Mees didn’t have a telephone at that time and the postal service was as yet non-existent. It came as a terrible shock to me and perhaps even more so to Adrie and Mees. I looked on them as my parents. As I was only 11 and had not seen or heard from my mother for about two years, it was as though I was going to be taken to meet a stranger. They packed my suitcase, we said goodbye and I promised to write soon. Off we went to Laren; I can honestly say this was one of the saddest days of my life.

I spent my entire first school holiday with Adrie and Mees and my mother also came down to Leerdam to meet them and thank them for all they had done for me.

After I went to England on 2 February 1947, we kept in constant touch by letter, telephone and visits until their deaths. Adrie died quite suddenly at the age of 60. Mees remarried and outlived his second wife. He died aged 92.